Geographies of Tech Wealth: San Francisco to "Silicon Border"

As the companies, workers and wealth of Silicon Valley creep north into the city of San Francisco, the effects of an industry with a relatively small but highly paid labor force are leading to widespread social unrest. Embodied in the symbolic protests around “Google Buses,” lower-income residents are reacting to tech’s ability to produce so much wealth that is thinly distributed to a small labor force, disinvested from local infrastructure (with private transportation), and funneled to comically useless purposes like the “Google Barges” mysteriously floating in the Bay. However, conversations about tech wealth are often limited to its distribution—with even mainstream economists (as well as The Economist) conceding that, “Facebook will never need more than a few thousand employees.” Clearly, the other side of this is production; even with its relatively small labor force, Facebook can generate billions in wealth and profits. Instagram, the hip photo sharing mobile application, famously had only 13 employees when it sold for $1 billion (that’s around $77 million per employee).

As the companies, workers and wealth of Silicon Valley creep north into the city of San Francisco, the effects of an industry with a relatively small but highly paid labor force are leading to widespread social unrest. Embodied in the symbolic protests around “Google Buses,” lower-income residents are reacting to tech’s ability to produce so much wealth that is thinly distributed to a small labor force, disinvested from local infrastructure (with private transportation), and funneled to comically useless purposes like the “Google Barges” mysteriously floating in the Bay. However, conversations about tech wealth are often limited to its distribution—with even mainstream economists (as well as The Economist) conceding that, “Facebook will never need more than a few thousand employees.” Clearly, the other side of this is production; even with its relatively small labor force, Facebook can generate billions in wealth and profits. Instagram, the hip photo sharing mobile application, famously had only 13 employees when it sold for $1 billion (that’s around $77 million per employee).

What is going on is not only a lack of distribution but an industry’s ability to generate massive profits without the need of a sizable labor force.

San Francisco: Canary of “Wageless Life”

If Detroit is the metropolitan victim of “deindustrialization,” then San Francisco is the victor of the “high-tech economy.” But the centrality of San Francisco in new modes of profitability is experienced in highly unequal ways. While the clashes between long-time residents and the inflow of high-wage “techies” are amplified by the geographic constraints of the San Francisco peninsula, this isn’t just a story about inequality, nor about a lack of housing supply as some cheekily imply.

More than inequality, San Francisco’s unrest stems from a population facing an economy that no longer needs them. Those being evicted from communities of color are not only facing gentrification but also perpetually low-wage labor in an economy that doesn’t need them to produce competitive profits.

Economist and presidential advisor Larry Summers made headlines early this year when he shared his fears of “secular stagnation”--effectively insufficient demand to grow the economy. But as Michigan economic sociologist Greta Krippner has pointed out, this is not a new process, since the rise of “financialization” in the 1980s was already a response to the economic stagnation that began in the 1970s in the U.S. It is in the context of what appears to be the geographic limits on U.S. profits (because of limits of domestic demand, global competition, and over production) that tech provides an avenue for profitability relatively unencumbered by the physical constraints of labor and time.

Working hand in hand with financial speculation, tech is the new industry with the promise of fixing the West’s “New Growth Conundrum.” Chillingly, as the eviction of Bay Area workers foreshadows, a larger economic transition may push a significant part of the domestic labor toward what Yale historian Michael Denning has called “wageless life.” For Denning, these are workers who are a “relatively redundant population,” or to borrow a term from a different context, “populations with no productive function [in the tech economy].” Demand doesn't seem to be the root problem as Summers suggests, as expansions in credit access and the household debt burden have long buttressed wageless demand.

Some might note that high-wage jobs in San Francisco aren’t the only jobs generated by the tech economy. This is true, and following the money of the information economy eventually leads one abroad.

“Silicon Border” and Microwork: The Travels of Tech Wealth

To say that tech and the information economy do not distribute wealth is not to deny that it travels. Of course, venture investments and speculative growth are enabled by flows of global capital. However, equally dynamic is the outsourced production of microchips and the novel “Impact Sourcing” or socially targeted “microwork,” both of which skip the domestic U.S. labor force and seem to be jumping directly to the global South, pre-branded as a poverty solution too!

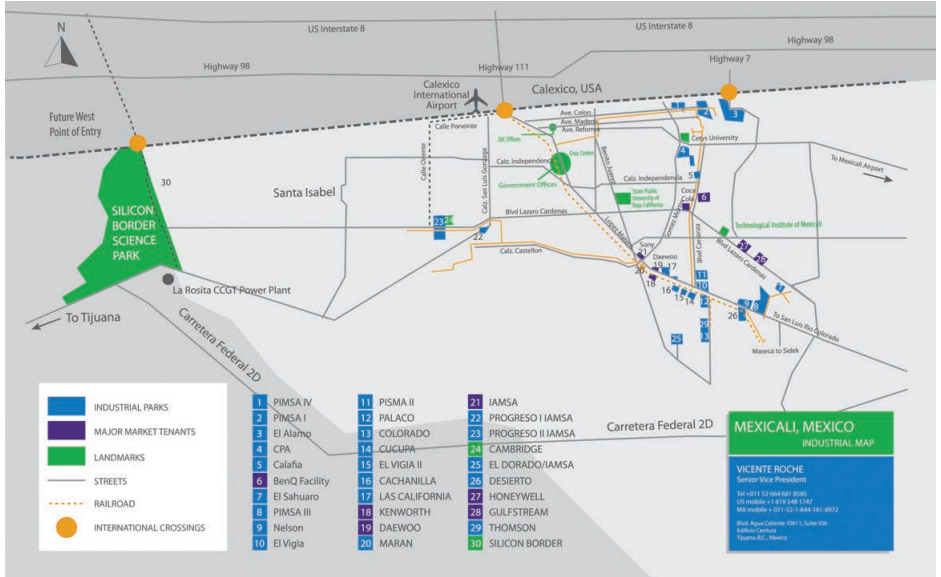

Tech wealth, in the form of wages, is distributed to somewhat familiar outsourced manufacturing sites. One peculiar example of tech wealth’s international travels is a 4,500-acre free enterprise zone in development not a mile south of the U.S.-Mexico border outside Mexicali. Dubbed “Silicon Border,” this commercial development is managed by the firm Jones Lang LaSalle, whose website prominently features their “2014 World’s Best Outsourcing Advisors” recognition.

Rendering of phase 1 of Silicon Border development, to include a “Science Park” as well as housing and a commercial units. Source: Silicon Border.

Marketing its first of four phases, investors seeks to attract tech industrial work for semiconductor manufacturing, boasting the site’s “Asian manufacturing cost structure in strategic North American location, [Mexican] Government incentives ranging from tax holidays […] free trade zone status […] with USA and 43 additional countries [and] access to reliable electric power, fresh water, waste water treatment and fire suppression systems [in the middle of the Yuma desert].”

Map produced by Silicon Border developers shows the massive scale of the development when compared to Mexicali, with a population of 700,000. Also, blue boxes represent other, smaller, manufacturing parks all built along international railways and international ports of entry. Source: Silicon Border.

If Silicon Border represents an adaptation of well-known models of securing cheap manufacturing labor abroad, the novel emergence of “microwork” is outsourcing with a social conscious. Microwork initiatives operating globally seek to build a business model around recruiting un- or underemployed workers to perform simple data-based tasks online (think of it as a global information assembly line). While the microwork model is in its infancy, it has already attracted companies like LinkedIn, Google, and Microsoft to this “pay-as-you-go” labor model. Differentiated from outsourcing with the brand “socially targeted sourcing,” this model is promoted as a 21st century solution to poverty that provides not only employment but equips workers with information and communication skills. In the words of the Rockefeller Foundation, social targeted sourcing generates both “financial and social value.” A report commissioned by the Rockefeller Foundation last year estimated that the market for microwork sourcing could rise to $20 billion by 2015.

Diagram mapping the locations of Impact Sourcing Service Providers, most operating in the global South. Source: Rockefeller Foundation.

Perhaps rather than questioning the distribution of tech wealth, we should question the terms of its production and forms of its global movements. The travels of tech wealth are dynamic, but profoundly uneven and unequal. As UC Berkeley MCP student Christina Gossmann shows, there even exists an extensive economy of electronic waste in the rubbish dumps of Kenya—a nation that is working to connect to streams of tech wealth by marketing itself as a potential “Silicon Savannah.” (Also see the Silicon Cape initiative in South Africa).

The eviction of working class families from San Francisco, and rise in inequality, should not be approached as a starting point, but rather as a symptom of a dangerous shift in production to rely heavily on tech wealth. The effects of this are not only domestic, but also unequally global, as this short article has suggested.

To quote artist and journalist Susie Cagle’s brilliant animation of the “class wars” in San Francisco: let’s stop talking about buses, “let’s talk money.”

Luis Flores is a Judith Lee Stronach Fellow at UC Berkeley and runs the Collective History Archive, an interactive oral history platform on debt, the recession, and the “New Economy.” He is a research intern at Causa Justa :: Just Cause. Luis can be reached at jr.luisf@gmail.com

Crowdsourcing 2.0: Why Putting the Slum on a Map is not Enough*

There was a time—not too long ago—when informal settlements the size of small cities were practically invisible. Large and empty beige-gray fields, intercepted by an occasional thin blue line, signifying water, and several thicker, windy white lines that stood for major roads, would pop up on the computer screen when searching for infamous slums such as “Kibera” on Google Maps. The information void stood in stark contrast to the hundreds of thousands of people living in Kibera, ironically tucked away between some of the city’s most valuable and celebrated resources: the Royal Nairobi Golf Club, Ngong Forest and the Nairobi dam.

There was a time—not too long ago—when informal settlements the size of small cities were practically invisible. Large and empty beige-gray fields, intercepted by an occasional thin blue line, signifying water, and several thicker, windy white lines that stood for major roads, would pop up on the computer screen when searching for infamous slums such as “Kibera” on Google Maps. The information void stood in stark contrast to the hundreds of thousands of people living in Kibera, ironically tucked away between some of the city’s most valuable and celebrated resources: the Royal Nairobi Golf Club, Ngong Forest and the Nairobi dam.

Googling Kibera would not reveal much information about the slum, but more significantly, information also lacked within the slum. In the eyes of the government, the slum did not exist or matter and only few stories, usually about gangs and murders with attention-grabbing sensational headlines bordering sinister hilarity, were deemed newsworthy. For relevant and current happenings, residents would therefore consult their social networks: neighbors, friends and family. As the extensive literature on social capital and intelligence has shown, who you know (rather than what you know) contributes enormously to slum dwellers’ complex networks of resilience.

But there are situations when those networks are simply not enough.

One of those situations presented itself on the night of the 30th of December 2007. After Kenya’s general election on the 27th of December, hopes—and polls—were at a peak for the opposition party’s Raila Odinga. But after a three-day delay, incumbent President Mwai Kibaki was unexpectedly pronounced the winner. What exactly happened next and who is to blame continues to be widely debated, but what we do know today is that inflammatory text messages and emails had played a major role in inciting the violence that lasted for two months, resulted in the death of over 1,000 people and the displacement of 350,000. Most of what would later be called “ethnic cleansing” took place in informal settlements, including Kibera, the same areas with the least access to information. Nobody knew whether and when it was safe to step outside the house. After only several days, a small group of programmers released software that would use the same tactics as the perpetrators of violence—SMS and emails—to create an alternative information-sharing platform. Ushahidi, Swahili for “testimony,” mapped reports of crime and violence that could easily be submitted and accessed online or by mobile phone. In both, the global South and its North, crowdsourced crisis-mapping has served as populist tool for asserting political contestation and for checking state violence, in effect producing a “politics of witnessing” at a global scale.

Open Street Map displays various resources in Kibera including hospitals and schools.

Ushahidi shined a spotlight on a long ignored problem: the lack of information on and for informal communities. Although constituting a significant urban demographic in cities of the Global South—and the majority in some, including Nairobi where an estimated 60% of the population lives in slums—slum residents are often ignored in planning processes and budget allocations.

With the goal to change the situation by literally putting Kibera on the map, an international development practitioner and a programmer founded MapKibera in 2009. Through support from local techies who helped train Kibera residents in using OpenStreetMap (OSM) techniques—including GPS surveying and satellite imagery digitizing—Kibera began making a geospatial appearance. In the years to follow, citizen journalism efforts ensued, developing atop the MapKibera information on OSM. The Voice of Kibera community news website and the Kibera News Video Network journalism project indiscriminately cover everyday Kibera, from local fires and elections to a marvelous Bulgakov-esque exploration of Kibera from a dog’s perspective.

Even today, few of Kibera’s resources appear on Google Maps.

The Ushahidi Platform places reports submitted via SMS and email on a map.

MapKibera was the first mapping initiative of its kind. By training local residents in geospatial data collection and visual storytelling through photography and video, MapKibera has significantly contributed to the democratization of media. It also made international news and brought much-needed attention to Kibera. Kibera’s data and founding members traveled the world, presenting their initiative and findings at research and innovation hubs. It was actually at one of those trips to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Media Lab where I first heard about MapKibera. Without a doubt, MapKibera’s approach and legacy for the Information and Communications Technologies for Development (ICT4D) community cannot be denied.

But is uncovering and making information publicly available enough? The most recent decision of the City County Council of Nairobi not to include informal settlements in the new Master Plan of the city—the first since 1973—indicates that it might not be. With a saturated map served on the OSM silver platter, neither the city nor residents seemed to make much use of it. The City insisted on a dearth of quality information, thus justifying its denial of actively planning for informal residents’ needs and wants in the city’s future development. Residents already knew the locations of basic mapped amenities such as schools, taps and pharmacies in their neighborhoods.

What was needed was information that would allow slum dwellers to assert political agency and claim access to basic needs such as decent housing, water, education and health care—citizen rights that are constitutionally backed since 2010. One example of pro-slum advocates moving towards this target-driven data collection direction is the Spatial Collective, a Mathare-based social enterprise, founded in 2012 by several experienced participatory mappers. Similar to MapKibera, the Spatial Collective benefits from Kenya’s mobile phone penetration rate--more than 77% of Kenyans regularly use a mobile phone--and widely available cheap Internet service to tap into an already existing information system to access local knowledge. They use this data to map slum resources but also their most basic needs. Crime and rape reports, for instance, allow for specific interventions such as installing lamps for safety. But before anything else, the Spatial Collective conducts a needs-assessment and baseline survey to evaluate whether what they do actually makes a difference.

As international development practitioners and technology enthusiasts forge ahead with increasingly popular crowdsourcing initiatives, I recommend the community engage not only in data collection, but in also purpose-driven, accountable data-collection that targets one particular goal at a time. A foreign-founded and partially–funded initiative, the Spatial Collective has drawbacks of its own. But if there is anything we have learned from ICT4D projects by now, it’s that nothing’s perfect.

Christina Gossmann is a Master of City Planning student at UC Berkeley. Before returning to graduate school, she worked as a freelance journalist and researcher in cities of the Global South. Email her at christinagossmann@gmail.com and follow her at @chrisgossmann.

*This story originally appeared, in a slightly different version, on Barefoot Lawyers International and The Con.

Fear and the Urban Form

“I don’t mind the American soldiers on our streets. If I could talk to them I’d ask: Why are you so afraid of us? Why do you fear us so much?”

So answered my Afghan friend, when I asked him how he felt about the American troops parading the streets of Kabul. I expected him to be appalled by the invasion on his privacy, or sovereignty. But what appalled him most was their fear, and how it seeped into his everyday life. When he looked at them too long, they pulled out their gun, he said. I thought the high walls and barbed wires of Kabul’s new architecture conveyed the same message.

Gated community in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Source: Tuca Vieira.

“I don’t mind the American soldiers on our streets. If I could talk to them I’d ask: Why are you so afraid of us? Why do you fear us so much?”

So answered my Afghan friend, when I asked him how he felt about the American troops parading the streets of Kabul. I expected him to be appalled by the invasion on his privacy, or sovereignty. But what appalled him most was their fear, and how it seeped into his everyday life. When he looked at them too long, they pulled out their gun, he said. I thought the high walls and barbed wires of Kabul’s new architecture conveyed the same message.

Anthropologist Teresa Caldeira, in her book City of Walls: Crime, Segregation and Citizenship in Sao Paulo, analyzes the escalation of crime in Sao Paulo since mid-1980s that generated widespread fear. This led to “new strategies of protection and reaction in the city, of which the building of walls is the most emblematic. Both symbolically and materially, these strategies operate by marking differences, imposing partitions and distances, building walls, multiplying rules of avoidance and exclusion, and restricting movement,” she writes.

Fear is an emotion induced by a perceived threat, and the perception of threat is dependent on many things – including, but not limited to, gender, age, sex, race, neighborhood cohesion, confidence in police, personal experience of victimization, levels of local incivility and financial conditions. In the previous examples fear is a result of the loss of power in structurally unequal relationships with a collective “other”, whether it is the U.S. military that elicits a fear of violent contestation or the wealthy elite in Sao Paulo. In both, the nature of the observer and nature of the observed environment influence one’s perception of threat. But the relationship between fear and our built environment is for me, most peculiar. Probably because it is hard to tell whether form follows fear or fear follows form.

Can we Design away Fear?

In Afghanistan, "HESCO Barriers" line corridors protected by sand barriers thick enough to withstand the impact of a car bomb. Source: NPR.

If fear indeed follows form, I am tempted to ask: Can we design away fear? There has been no dearth of attempts made in the past to do this.

After the Industrial Revolution, modern architecture sought to assuage the fear generated by rapid industrialization and urban problems of ‘disorder’ – giving birth to modernism. The profession of planning meanwhile diverged from its initial agenda to become primarily curative rather than preventive or formative. Postmodern urbanism sought to improve upon the shortcoming of modernism and to respond to the peculiar nature of fear that it in part caused. But it ended up falling in the same traps (see Nan Ellin's 2007 Architecture of Fear).

Architect Nan Ellin says in Architecture of Fear, “Contemporary insecurity has elicited a reassertion of cultural diversity, nostalgia for an idealized past, an infatuation with mass imagery, flights into fantasy worlds, a marked privatism, and a spiritual turn. In urban design, these tendencies are primarily manifest as historicisms, regionalisms, and allusions to mass culture.”

The contemporary focus on crime and safety in relation to the built environment began with the American-Canadian journalist, author and activist Jane Jacobs in the 1960s. To her, a safe city was the traditional city with streets and blocks, diversity, functional mix, concentration and buildings of different age. Her observations were astute but without systematic empirical evidence.

In 1972, architect Oscar Newman developed a more targeted response to safety through design, with the concept of Defensible Space. His answer to the problem was introducing a more graduated territoriality through the creation of semi-public and semi-private spaces – and to some degree, by putting up fences. His work was evidence-based with, for instance, detailed spatial descriptions and statistics.

But can crime really be prevented through environmental design? It is a question open to debate. Any effort to understand the relationship between fear and the built form based purely on empirical evidence is futile, because actual crime figures do not present the whole picture. Let me illustrate with an example.

Take a neighborhood with very sophisticated surveillance, security systems and 24-hour guards. Measures that make impossible for one to bat an eyelid without someone cooped up in a surveillance room knowing about it. Actual crime rates are reduced to a minimum here. But is this an ideal living environment? Are we not bargaining our sense of security for our sense of freedom? Are we not compromising our ‘right to the city’?

Secure but Segregated

The latest and perhaps more extreme reaction to the problem of crime and fear of crime in cities are enclosed housing developments, often called gated communities. A gated community is a housing development on private roads closed to general traffic by a gate across the primary access. The development may be surrounded by fences, walls or other natural barriers that further limit public access. These housing developments have become popular in some severely crime-ridden developing countries, such as South Africa and Brazil but to a large degree are also found in the USA, where more than seven million households (about 6% of the national total) are in developments behind walls and fences.

Developments of this kind create spaces that contradict the ideals of openness, heterogeneity, accessibility and equality. This is fairly evident in the city of Los Angeles. Like in many other global cities, as the economic disparity deepened over time so did the lines of segregation. Most of L.A.’s public life takes place in segregated, specialized and enclosed environments like malls, gated communities, entertainment centers and theme parks. Many of these changes in urban environment are furthering separation between social groups that are increasingly confined to homogenous enclaves. The consequences of this new ‘separateness’ can be drastic. Defensible architecture and planning may end up promoting the same conflict that it was intended to prevent.

Freedom from Fear

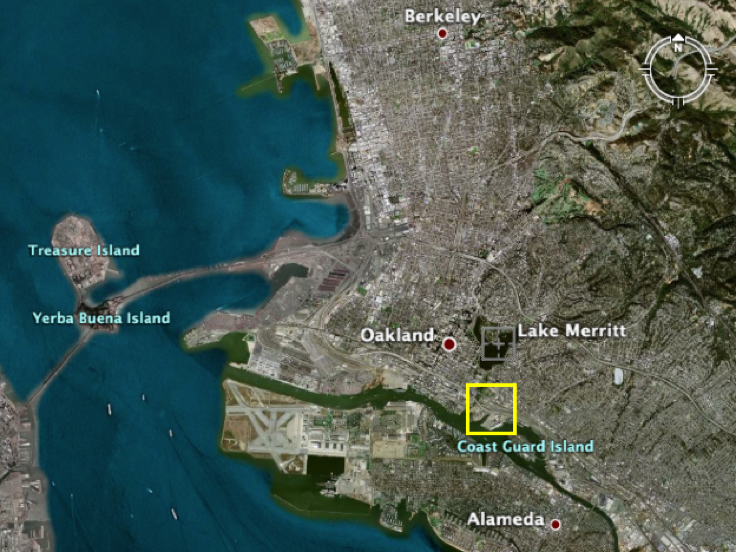

The city of Oakland recently received $7 million from the federal government initially intended to deter terror attacks at the port of Oakland. Instead, these funds are being used by a Oakland police initiative that will collect and analyze surveillance data. Source: Globalresearch.org

Different cultures have different ways of fearing. The meaning a society attaches to the fear of God or the fear of hell is very different from the fear of pollution or the fear of cancer. As Frank Furedi explained in “Culture of Fear”, we associate fear with a clearly formulated threat and today we represent the act of fearing itself as a threat.

In that sense we are all victims, even if we have not personally experienced an act of crime, since we are all aware of it, and live in fear of it. This is a fear we are reminded of every day in media, daily conversations and sub-consciously, through our environment. This fear infringes on our everyday behavior, activities, sense of security but also freedom.

As architects and designers, we need to view the issues of safety and fear from a new lens. Maybe crime prevention alone is not a solution. An alternative to ‘gatedness’, a neighborhood that is secure but not segregated, needs to be imagined, if we hope to finally reach the root of the problem.

Tanvi Maheshwari is a Master of Urban Design student at UC Berkeley. She is currently pursuing her thesis on the subject of fear and its relationship to urban form in the Indian context.

She can be reached at

.

The Significance of Community in Modern Planning Theory

David Chavis’ 1990 article, “Sense of Community in the Urban Environment: A Catalyst for Participation and Community Development," highlights the effects that perception of environment, social networks, and how residents’ sentiments about their communities can further influence the behaviors and perspectives of others. The article further emphasizes the importance of citizen participation in community organizing and explains why it has been regarded as key to improving the quality of the physical environment, enhancing services, preventing crime, and improving social conditions.

Reflections on: "Sense of Community in the Urban Environment: A Catalyst for Participation and Community Development," by David M. Chavis

David Chavis’ 1990 article, “Sense of Community in the Urban Environment: A Catalyst for Participation and Community Development," highlights the effects that perception of environment, social networks, and how residents’ sentiments about their communities can further influence the behaviors and perspectives of others. The article further emphasizes the importance of citizen participation in community organizing and explains why it has been regarded as key to improving the quality of the physical environment, enhancing services, preventing crime, and improving social conditions.

I view the institution of a locally-driven planning process as being essential to the establishment of a general sense of community. The maintenance and enlargement of self-sufficient, self-governing bodies (community organizations), further signify the additional role that empowerment has in local development. According to Chavis, a working definition of the term “sense of community”, suggests local processes of development that create opportunities for membership, influence, mutual needs to be met, and shared emotional ties and support. Essentially, a sense of community points to the strength and shared benefits of social capital. The more invested we are in community, the more power and ownership we feel we have in the communal environment. It is through this process that a sense of community contributes to individual thought for collective development.

I find it immensely intriguing, that when we compare communities that seem to be thriving, both socially and politically, to low-income communities, plagued with the accompanying concerns of crime, disinvestment and unemployment concentrated in a single area of poverty, one tends to wonder if there is a specific criterion of that qualifies it. Trends in both these specific communal types seem to possess a constant, regardless of country, city, location, ethnic makeup, etc. However one might evaluate the success of a community, the residents of perceivably well to do communities possess a notably stronger sense of community, than do residents of less socio-politically affluent communities. This sense of community therefore compels residents to develop and maintain social networks, in addition to in social capital. This investment in social capital is yet again, another product of that sense of community. A sense of community can have a great influence on one’s desire to control or contribute to the environment, often helping to address problematic concerns that may be regarded as problematic. For instance, I view the formulation of this ‘sense of community’ as being instrumental to the effectiveness of the Occupy Movement. A collective effort, with one voice, and a common goal. The control or occupying of space is but a means by which to establish an improvised locale for a “quartered” community. The resolve to maintain these claimed spaces was clear in the emergence of riotous protest as Occupiers clashed with law enforcement (in their attempts to divide the urban community, before conquering the social community). Another example of this can be seen in 1957’s, Little Rock’s Nine during the integration of Central High School. The local community viewed academic integration as problematic. When the National Guard intervened, (an additional group of “outsiders”) to enforce the law, the resistance became unpredictably explosive.

Although the concepts of Social Capital and Networks could quite easily take us into totally separate discussion altogether, in this context, I view social capital and social networks as being interdependent. Social capital deals with the product, the talent, skill or unique ability one contributes to the greater community with which he holds membership. Social networking speaks to the ways in which members of that community bargain to benefit one from another by the utilization of this collection of gifts and talents. All these are major players in the establishment and maintenance of a sense of community.

Apart from physical features, one of the key distinctions between these community types is the length to which residents will collectively go to protect “their” society. Examples of this are seen in high-price residential communities like Pleasanton, CA. for example. A highly expensive neighborhood where the rent you pay for a 2-3 bedroom condo, could match that of the cost of a home mortgage in parts of a city like Oakland. The economic support or disinvestment in local businesses is another way communities might protect their neighborhood. According to Chavis, perceived control relates to the beliefs an individual has about the relationship between actions (behavior) and outcomes.

The protection of a society further suggests that there are boundaries involved. These boundaries could be physical barriers such as gated communities, rivers, railroad tracks; or even socioeconomic barriers such as highly priced property, educational requirements, and other forms of exclusive criteria. These boundaries form due to society’s perception of “the other”. Therefore, in order to retain some sense of emotional security—to live without fears—communities tend to form boundaries in which to maintain, occupy, and repel others from entering.

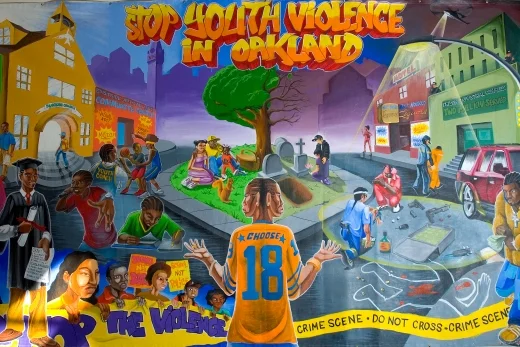

Working to help establish a sense of community in modern planning today should be held as a vitally important aspect of the planning process. The mural below depicts this perfectly. It was designed by a youth empowerment program in Oakland CA, Youth UpRising. The youth of Castlemont were included directly in the planning process. This mural is a reflection of what the young people view as the areas of concern in their community and what they actually want their community to evolve into. Considering the impact that community and developmental endeavors can have on the outcomes of specific regions, in order to further eliminate the formation and spreading of concentrated despair, community building must become a more integral part of the planning process.

Julian Collins is interested in topics of housing, community and economic development. He received his Bachelors from the University of Illinois, Chicago in Urban and Public Affairs and is now pursuing a Masters at the UC Berkeley in City and Regional Planning.

Bogotá’s Bucolic Exodus: Aspirations of a Rural Life or Suburban Sprawl?

Yearning for a rural lifestyle is a legitimate desire for all city dwellers. It is more than understandable to think about a nicer place if you can afford it, considering that “nicer” often means more greenery and nature. Nevertheless, countryside living is not only an aspiration for people in Bogotá who are planning a systematic exodus from the city’s current sense of collapse, but also for displaced rural people who try to make a living in the city. Sometimes there is a situation of urban dwellers colonizing farmers’ land, or the current national social illness of forced displacement.

Yearning for a rural lifestyle is a legitimate desire for all city dwellers. It is more than understandable to think about a nicer place if you can afford it, considering that “nicer” often means more greenery and nature. Nevertheless, countryside living is not only an aspiration for people in Bogotá who are planning a systematic exodus from the city’s current sense of collapse, but also for displaced rural people who try to make a living in the city. Sometimes there is a situation of urban dwellers colonizing farmers’ land, or the current national social illness of forced displacement.

In Bogotá, like in many cities, transportation deficiency, generalized security concerns in many areas and the increasing cost of living are negatively influencing the everyday experience of its citizens. It is therefore perfectly reasonable to consider moving to a place where the pace of daily activities is slower, groceries are cheaper and air is cleaner. Large cities and capitals offer job opportunities, cultural exchange and superior levels of health and education that do not exist in rural areas. In this sense, despite its utilitarian purposes, the city has become increasingly unaffordable, insecure and threatening, especially for rural migrants.

La Calera, for example, is one of the “rural” paradises desired by high-income people in Bogota, and utterly pursued as a pot of gold by real estate developers. However, this place is one of the city’s principal natural reservoirs, in terms of water supply and green areas. If Bogotans continue running away from the city to settle permanently in a place that is geographically guaranteeing our city subsistence, we are threatening urban collective survival. And on the other hand, people that are actually living in places like this cannot migrate to the city with no credit history or any urban expertise, because life in the Colombian countryside is just too different.

Displaced communities in Downtown Bogota. Source: RCN La Radio

How do we interpret the trend of urban dwellers dreaming of the countryside and rural dwellers being forced to move to cities? Will we see Colombian cities filled with “for rent” signs and rural parcels abandoned or used for suburban homes, violating not yet written environmental policies? For a poor peasant for example, starting from scratch in a city like Bogota can lead to a sense of not belonging. Working in minimum wage jobs, whether in the formal or informal sector sometimes results in resignation, resentment and even violence, as a consequence of being forced to obey a system that apparently has not been designed for equality. In this sense, the question would be if this two-way rural-urban migration corridor is leading to any collective improvement for any of the participants involved.

Maybe visualizing these possible outcomes of current mobility trends can help us achieve a balance. If there is no urban expansion, inner city land values will be increasingly raised to the point of absolute unaffordability, but at the same time, suburban sprawl has a huge impact on ecology and demand for infrastructure that is equally destructive. On one hand, real estate speculation of suburban developments is supplying housing demand for high-income households only. And on the other hand, barely legal urbanization in risky areas of the city is only supplying housing lots for many of the low-income people that are coming into the city as cheap labor. This way, both the high-end suburban housing and the informal inner city housing seem like extreme responses to these recent moving trends.

La Calera suburban housing. Source: SkyscraperCity.com

Maybe it is about public policies that ensure affordable housing for all citizens, regardless of their incomes. Or it might be about adaptability. Bogotá could (and should be) more inclusive for migrants by providing jobs and housing opportunities, whether they come from the countryside, from other cities, and even from other countries. Also, maybe the city can offer better conditions so its actual inhabitants don’t feel the urge to escape. Probably cities can be understood beyond the utilitarian aspects of just being destinations for concentrated job opportunities. In this manner, the urban experience could be positive for all. What if we bring more high quality services to the countryside and bring more environmental qualities to our cities? This way we might not be forced to endure this polarization of individual needs that are turning migration processes in Colombia into an evident symptom of inequality.

I envision a more inclusive Bogota indeed. And this probably demands a deeper understanding of the rural-urban mutual dependency, for both in citizens and policy makers. In this sense, some of the government’s efforts providing affordable housing for rural migrants are strategies of more equitable policies that somehow still seem insufficient. This raises the question about the causes of these inequity indicators in Colombia’s capital. Will affordable housing ever be enough and what will happen when the city runs out of land? Is increasing new housing supply the solution for a larger scale political conflict that is massively displacing people from our most forgotten rural areas? And on the other hand, how can policies also regulate this recent trend of suburban sprawl that is also taking over the countryside? Maybe this recent circular migration pattern is an opportunity to visualize how a city embodies the illnesses of a country. But also, an invitation to ask ourselves: Is moving the solution? Where will these exoduses lead us to?

Maria Luisa Vela is a first year graduate student at UC Berkeley, pursuing a Masters in Urban Design. She is a practicing architect from Bogota, Colombia and is currently interested in the relationships between public space and housing typologies for designing better neighborhoods in Latin American cities. She can be reached at marialuisavela@gmail.com

Redefining Shrinking Cities

Shrinking cities have been the subject of much conversation in recent years. With Detroit filing for bankruptcy protection and the growing concern about aging cities in Europe, the discussion is gathering ever more momentum. In a climate of hasty blanket statements and one-size-fits-all solutions, Aksel Olsen takes a step back to critically examine the phenomenon of shrinking cities, in order to find real, practical solutions.

A significant number of cities and regions across the US and Eastern Europe currently face population decline, economic contraction, or both. The ‘greying of Europe,’ where nearly a third of the population will be 65 or over by 2060, is increasing pressure on social services, urban infrastructure, and the labor supply.

In Volume 26 of the Berkeley Planning Journal, Ph.D. student Aksel Olsen’s ‘Shrinking Cities – Fuzzy concept or useful framework?’ enters the debate on urban decline. In this post, Masters of Urban Design student Tanvi Maheshwari explains why practitioners should look beyond simplified versions of the shrinking cities phenomenon.

Shrinking cities have been the subject of much conversation in recent years. With Detroit filing for bankruptcy protection and the growing concern about aging cities in Europe, the discussion is gathering ever more momentum. In a climate of hasty blanket statements and one-size-fits-all solutions, Aksel Olsen takes a step back to critically examine the phenomenon of shrinking cities, in order to find real, practical solutions.

A significant number of cities and regions across the US and Eastern Europe currently face population decline, economic contraction, or both. The ‘greying of Europe,’ where nearly a third of the population will be 65 or over by 2060, is increasing pressure on social services, urban infrastructure, and the labor supply. The trend is raising new concerns for planning and design, such as how to create different types of mobility structures for the elderly population. For Eastern European cities, the out-migration of young workers seeking better employment opportunities has made the equation even more difficult. As tax bases shrink, planners and politicians in both the US and the EU will need to attract and retain a younger workforce, in part by reforming immigration policy, and make the urban environment accessible for the elderly.

Percentage of Population over 65 in Europe. Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Europe_population_over_65.png.

Shrinkage is not a new phenomenon. During the post-war years in the US, the middle classes fled in hordes from dense city centers to rapidly developing suburbs, aspiring for space and racial homogeneity, thus hollowing out the city cores. In the present context, however, intra-city shrinkage is not planners’ primary concern. In fact, many American suburbs are shrinking as well. Cities in the Rust Belt grew in an era when large-scale manufacturing required large amounts of labor. With much of their traditional labor force no longer as in demand in the modern economy, many Rust Belt cities such as Detroit face population and economic decline. Leaders in these cities have attempted different strategies, with varying success, to reinvent their image and their economy around creative industries, a manufacturing renaissance, or the service sector.

Decline of Detroit. Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Abandoned_Packard_Automobile_Factory_Detroit_200.jpg.

But shrinkage today is a complex phenomenon, not limited just to the Rust Belt. It is afflicting much more heterogeneous regions, including those around the Californian cities of Fresno, San Francisco, and San Jose. It should be noted that the time period when shrinkage was observed in these cities mostly coincides with the 2001–2002 recession. During this time, San Jose did indeed lose population at a rate of three per thousand or so for a two-year period. However, while the rate of population decline was at about three per thousand in 2002 and 2003, the number of occupied housing units appears to have increased over the same period at a rate of seven per thousand. This may mean that the shrinkage observed is San Jose may just a change is demographics, like change in size of household. It may not be valid to call San Jose a shrinking city, as shrinkage may be just a temporary result of a city in flux.

Aksel Olsen’s paper argues that shrinkages in Eastern European cities, the Rust Belt in the US, and in the Californian so-called “Sun-Belt” cities are not comparable. In fact, bundling them together creates a fuzzy definition, watering it down to the point where it is no longer useful to describe the vastly different trajectories of urban evolution. The scholarly definition of shrinking cities is ‘a densely populated urban area with a minimum population of 10,000 residents that has faced populationlosses for more than two years and is undergoing economic transformations with some symptoms of a structural crisis.’ A tighter definition, taking into account specific contexts, would be more helpful to planners.

The typical definition of a “shrinking city” is flawed in two key ways. First, it fails to distinguish shrinkage due to an aging population from shrinkage due to shifting industries. Each requires different policy strategies. A lower fertility rate may be a long-term problem, but in the short term, the migration balance matters more because it has a greater effect on the economically active population. Further, a thriving city center may still experience population growth despite industries moving out. The San Francisco Bay Area during the Dot Com Crisis of the years 2000–04 would be an example of population growth and a changing job base. This distinguishes a Detroit from a San Francisco.

Second, the typical definition of shrinking cities is too shortsighted. Planners should look at the long term. Olsen equates short-term forecasts of “shrinkage” to comparing ‘weather’ with ‘climate’, one representing short-term changes and the other, long-term structural changes.

A city with a rapidly growing economy might shrink deliberately, to create a better quality of life for a smaller population, or may going through a phase of transition. In the 1980s, Pittsburg began to focus on high-end retail. Pittsburgh seems to be in the midst of a transition to an entertainment economy, even as the city continues to lose population, again underlining the complex patchwork of prosperity and decline, here at the city scale. Despite half a century of population loss due to industrial decline, Pittsburgh is, if not thriving, certainly outperforming both the Rust Belt and the nation as a whole. Its unemployment rate of 7.8% is well below the national average.

Pittsburgh Skyline. Source: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pittsburgh_Skyline.JPG.

Should shrinking cities then be defined as simply a state of being, defined on the basis of population loss or job loss? Or should a deeper investigation be made into its underlying causes? The latter is essential, if the city has to devise policy directions to deal with the situation. Growth and decline are a part of the natural cycle of a city’s life. If short-term fluctuations are assumed to reflect broader trends, urban policy-makers will fail to identify the true causes of shrinking cities resulting in uninformed policy decisions and a trivialization of the issue. Planners should think about ways to preserve affordable housing to prevent gentrification when there is rapid growth occurring.

Olsen’s paper left me convinced that contextual analysis, that is, a qualitative typology to define shrinking cities instead of a quantitative one, would lead to more useful observations. These can serve as a comparative framework for analyzing similar cities worldwide. A qualitative approach leads to more relatable comparisons between shrinking cities of erstwhile East Germany and the Rust Belt in the US, instead of the Sun Belt.

I would argue for uncoupling ‘prosperity’ from ‘ever increasing growth’, and urge cities to plan for ‘smart decline.’ Shrinkage may not always be a bad thing. In the words of Aristotle: “A great city should not be confounded with a populous city.”

Tanvi Maheshwari is a Master of Urban Design student at UC Berkeley. She is interested in urbanism of the global south and segregation in the public realm. She can be reached at tanvi@berkeley.edu.

The Battle of Baxter Creek: Resolving Power Struggles in a Community Green Space

This is a tale of a well-intentioned stream restoration project in a residential park-neighborhood of Richmond, CA that sparked a community power struggle. The unintended consequences of the restoration left the neighborhood divided. Neighbors who wanted to reduce criminal activity in the park were pitted against those attempting to promote local pride with aesthetic improvements. It provides an interesting case study bothfor understandingsuccessful urban creek restoration and neighborhood-level politics.

This is a tale of a well-intentioned stream restoration project in a residential park-neighborhood of Richmond, CA that sparked a community power struggle. The unintended consequences of the restoration left the neighborhood divided. Neighbors who wanted to reduce criminal activity in the park were pitted against those attempting to promote local pride with aesthetic improvements. It provides an interesting case study bothfor understandingsuccessful urban creek restoration and neighborhood-level politics.

Booker T. Anderson Jr. Park is a family-oriented green space serving a neighborhood located in Richmond, CA -- a city with high levels of crime. Beginning in the year 2000, an unappealing, blighted, channelized stream crossed the park that separated the park’s community center from a playground, soccer and baseball fields. Lisa Owen Viani, then graduate student at UC Berkeley, developed a project to transform this eyesore to a riparian green space, including a lush thicket of native willows based on regional heritage.

However, as time passed, the design’s obstructed sight-lines resulted in unintended public safety issues. One incident involved a police chase of an armed individual who fled into the understory of the willow thicket as kids were playing in the nearby playground and fields. This situation created a heightened fear of the willows among residents and park users. It also alerted the police to this area as a potential zone forcriminal conduct. Residents also reported increased muggings and drug and sexual activity in the area since the landscape project was implemented.

In the summer of 2007, while the director of the Parks Department was on leave, department staff responded to an outpouring of complaints by commissioning a “city maintenance crew who’d clear-cut everything below about five feet,” according to the Berkeley Daily Planet, which dubbed it the Richmond “Chainsaw Massacre.” While this resulted in improved sight lines that addressed the safety concerns of both the neighborhood and police department, some residents believed this to be a misallocation of limited resources that diminished the positive effects of the restoration.

It is important to understand how this community power play surrounding the stream restoration evolved. The seeds of this battle were sown over a decade ago when Lisa Owens Viani gathered support from a consortium of citizens, scientists, government and non-government agencies, including the Urban Creeks Council (UCC) and the City of Richmond. The UCC and the Friends of Baxter Creek received $150,000 to restore the storm drain to a ‘natural’ creek with riparian vegetation. At the time, typical restoration practice was placed-based. This method restores habitat to an historic state that once existed, from which plant and wildlife succession would follow naturally. Historically in the Bay area, many low-elevation streams were dense with thickets of willows. Using this method, the creek became a thriving ‘natural’ area that benefitted the ecosystem and the neighborhood, as well as providing a sense of identity among organizations from multiple local, regional, and state community interests.

In the ensuing years, the willows began to dominate the urban stream and the project soon became problematic for the community. The dense thicket of trees was no longer perceived as a safe place for children to play along the banks of the creek to catch tadpolesand butterflies. Several public meetings were held during the initial development; however, not all interested parties felt that the city had given them an accurate portrayal of how dense the thicket would become, a factor that contribute to the concerns of both the neighborhood and police department.

In reality, the 2007 “Chainsaw massacre” only destroyed eight willows out of several hundred on the project site, while the remaining trees were merely trimmed to allow for protective sight lines. But, after the uproar, a stakeholders’ meeting was quickly organized by the leader of the original project, Lisa Owens Viani, and supporter Ann Riley, a well-known stream restorationist and staff member of the Water Board. At that meeting, City Council member Tom Butt said that some members of the community desired ‘natural’ growth while others favored surveillance-ready spaces. He pointed to a gap in communication between planners and neighborhood stakeholders such as the local Neighborhood Watch group. This lack of communication ultimately prevented all of the stakeholders from coming to an agreement as to what defined a desirable park.

After the dust settled on Baxter Creek, valuable lessons emerged for planners, restorationists, and the surrounding neighborhood. The traditional historical ‘place-based’ method of restoration is not always the best for a given community. The sociological environment of the neighboring community is a key element in a successful restoration project. Tailoring the project to the needs of the neighborhood is as important as selecting the type of plants and wildlife to returning a creek to an enduring and healthy state. In addition, a plan needs to account for the maintenance of the restoration over time.

As it turned out, the City responded by funding $60,000 to further investigate neighborhood concerns, supplement the willows with a flowering chaparral understory (a novel approach in contrast to traditional riparian planning), and maintain four safety sight lines between the community center, playgrounds, soccer and baseball fields. The UCC immediately began their outreach to residents, which included door-to-door and mail surveys, along with four community meetings held over the course of a year. In 2008, an agreement was reached to construct a written management plan that would address the interests of all stakeholders, any change in maintenance crew protocols, and turnover among governing bodies. Since then the rancor from the Baxter Creek power struggle has subsided. Good landscape projects require prudent planning. From this experience, future landscape designers can take-away valuable lessons about the need to tailor restorations to a given community and ensure that they will be maintained over time.

Ken Schwab is an undergraduate of the University of California, Berkeley, where he is majoring in Conservation and Resources Studies at the College of Natural Resources. He is currently working an honors thesis, funded by SPUR and mentored by Dr. Vincent Resh, on the longest post-project monitoring of a ‘daylighted’ urban stream which includes: community perception, biological and habitat assessments, and a pioneering economic evaluation. He is actively involved with the Strawberry Creek Restoration, with Dr. Katharine Suding, which received a grant from The Green Initiative Fund (TGIF) -- Fitting Plant to Place: Site-Specific Restoration Planning on Strawberry Creek. Ken can be reached at ken.schwab@berkeley.edu.

Vestiges of San Francisco’s Unbuilt Waterfront

San Francisco has oftenserved as a blank canvas since its rapid rise to prominence after the Gold Rush in the mid-1800s – the subject of countless visions for how the built environment should be designed. Whilesomewereoutlandish and others more grounded, the many ideas advanced over the years for guiding the City’s development have each presented a roadmap for moving forward, complete with nested values of what is most important for the future. Such is the subject ofUnbuilt San Francisco – an exhibit currently presented at five locations around the Bay Area, including at UC Berkeley (more details below). On display are plans, renderings, models, and other media depicting unrealized visions for the San Francisco Bay Area. Some of these proposals, such as a BART line running into Marin County, many wish had been built; others, like Marincello, a 30,000-person community in the now-preserved Marin Headlands, we cannot imagine advancing today. The exhibit covers a journey of great breadth, ultimately leaving the viewer with anuneasy sense of what could have been.

San Francisco has oftenserved as a blank canvas since its rapid rise to prominence after the Gold Rush in the mid-1800s – the subject of countless visions for how the built environment should be designed. Whilesomewereoutlandish and others more grounded, the many ideas advanced over the years for guiding the City’s development have each presented a roadmap for moving forward, complete with nested values of what is most important for the future. Such is the subject ofUnbuilt San Francisco – an exhibit currently presented at five locations around the Bay Area, including at UC Berkeley (more details below). On display are plans, renderings, models, and other media depicting unrealized visions for the San Francisco Bay Area. Some of these proposals, such as a BART line running into Marin County, many wish had been built; others, like Marincello, a 30,000-person community in the now-preserved Marin Headlands, we cannot imagine advancing today. The exhibit covers a journey of great breadth, ultimately leaving the viewer with anuneasy sense of what could have been.

In the 1960s, a large planned development was proposed to be built in the Marin Headlands by the Gulf Oil Corporation. In the face of strong opposition from various environmental groups, in 1972, the company reluctantly sold the land so it could be incorporated into a new national park – the Golden Gate National Recreation Area. Source: Thomas Frouge, developer

The lasting impact of the Unbuilt San Francisco exhibition, though, is not simply an understanding of the Bay Area’s various unrealized futures, but more fundamentally an appreciation of how the choices made in the past impact how we see things today.

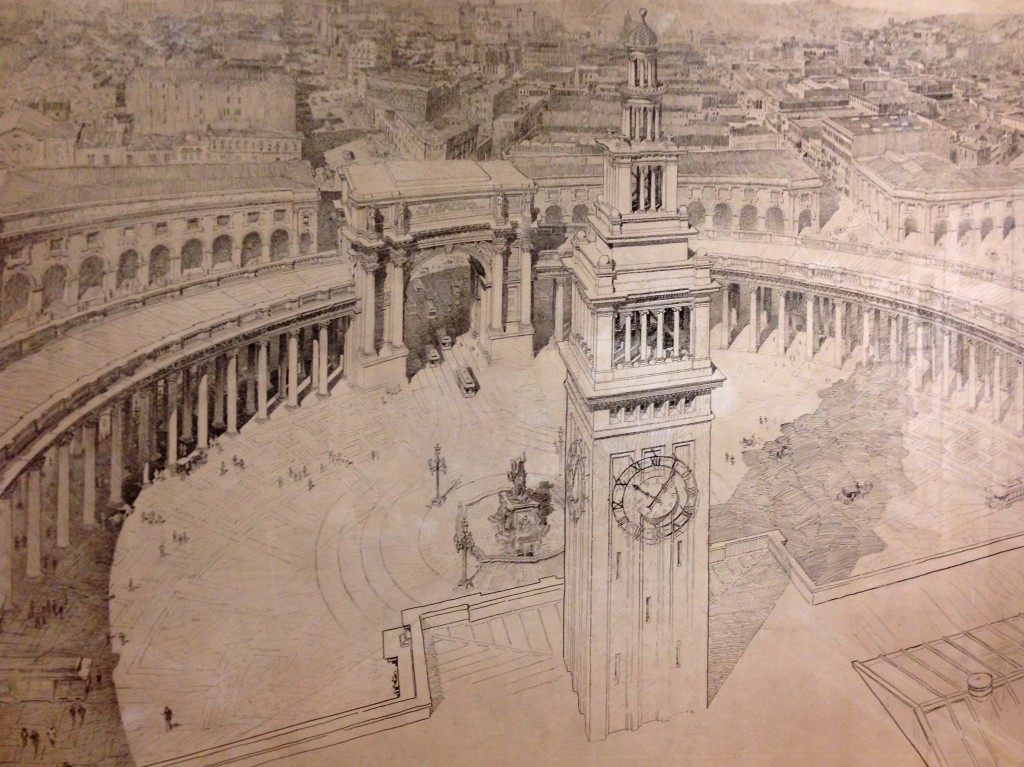

San Francisco’s ever-evolving waterfront is an excellent case study. Indeed, the edge of the Bay might have turned out quite differently than what we see today. A turn-of-the-century plan imagined the Ferry Building at the foot of Market Street surrounded by towering Roman-style columns. Decades later, another would have replaced San Francisco’s beloved waterfront monument with a modernist-inspired World Trade Center, surrounding a large sun dial. These ideas may sound outlandish today, but they were seriously considered at the time.

This turn-of-the-century vision would have created a grand public space in front of the Ferry Building encircled by classically-styled columns and arches. Source: Willis Polk (1897)

Another vision would have done away with the Ferry Building altogether and replaced it with a modern World Trade Center. The slender center tower and sun dial seem to allude to the structures they would have replaced. Source: Joseph H. Clark (1951).

One idea in particular has had an enduring influence on how we envision the waterfront today: the proposal for an elevated high-speed motorway running the length of the Bay’s shoreline.

In the 1950s, following the national trend, an ambitious network of limited-access freeways was conceived for San Francisco, crisscrossing all corners of the 7-by-7-mile city. Despite being swept up by the freedoms of automobility, freeways were far from welcomed in San Francisco. As the first few structures went up, including the double-decker Embarcadero rising between Market Street and the Ferry Building, people began to realize the damaging effects the roads were having. In swift response, the now famous Freeway Revolt was born.

Citizens crowd into City Hall wearing signs on their heads to express their opposition to the freeways being erected all over San Francisco. Source: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library.

Freeways in San Francisco were opposed for various reasons, but much of the discourse centered on aesthetics and access. Beyond being unsightly, neighborhoods that received the early motorways were walled off from their surroundings and quickly succumbed to blight and loss of vitality. After years of fierce opposition, the citizens' revolt was ultimately successful in blocking most proposed freeways, and the Embarcadero was only partly completed (it was originally proposed to connect with the Golden Gate Bridge). Just 21 years after the Embarcadero’s completion, it took only seconds for the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake to damage the structure enough to warrant taking it down. Though many enjoyed the access it provided and called for reconstruction, then-Mayor Art Agnos envisioned a new aesthetically-pleasing waterfront, and fought for the freeway to be replaced with the grand boulevard we know today. Few look back longingly.

Citizens crowd into City Hall wearing signs on their heads to express their opposition to the freeways being erected all over San Francisco. Source: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library.

The unrealized vision for a complete freeway network in San Francisco has left citizens sensitized not only to future roadway proposals, but also to any project that might possibly impact the waterfront’s aesthetics, access, or views. One need look no further than the controversial 8 Washington project rejected by voters earlier this month – what would have been a 134-unit luxury condominium development along the waterfront, adjacent to where the Embarcadero Freeway used to stand – to see this. The project had diverse opposition – from those who questioned building $5 million condos in a city struggling to provide affordable housing,to those who criticized its parking ratios – but most discourse concerned appearance and accessibility. Critics focused on the project's 13-story height, roughly twice that of the late freeway, claiming it would have blocked views and access to the Bay, thereby tarnishing the waterfront’s appeal.

This rendering, drawn up by supporters of 8 Washington, takes an elevated perspective, showing the tall buildings of the Financial District in the background, to downplay the project’s heights.

The opposition's image instead takes a ground-level perspective, juxtaposing the Embarcadero Freeway in front of 8 Washington, to illustrate the development’s towering design.

In typical San Francisco fashion, the 8 Washington debate became so heated that it was the subject of not one but two propositions on the November ballot earlier this month. Voters were asked if they approved of the decision to allow the project to exceed existing height limits. The ‘No on B & C’ campaign strategically employed the slogan “No Wall on the Waterfront” and made direct comparisons to the Embarcadero Freeway (campaign ad embedded below). Former Mayor Art Agnos reemerged as a spokesperson for the opposition, proclaiming that “8 Washington will be the first brick in a new wall along the waterfront.” Despite the obvious differences between the fallen freeway and 8 Washington, people were concerned that the progress made along the waterfront in recent years would be lost if the proposal moved forward. Ultimately, both initiatives were soundly voted down almost two-to-one. The developer may choose to return with a new down-sized proposal, but at least this version of 8 Washington joins the list of San Francisco’s unrealized visions.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cujWdElxCHk#action=share

Ideas remain unrealized for many reasons – because they do not match prevailing values, they were not well-conceived, or perhaps they just were not well-articulated – but some nevertheless persist, influencing decision-making to this day. The many unbuilt visions for San Francisco’s waterfront have not only influenced what was actually built, but have left a more enduring impact on how people imagine its possible futures. Turning over the waterfront to the purely utilitarian role of moving automobiles was ultimately rejected, replaced by a more aesthetically-focused public space. The discourse surrounding this unbuilt vision continues, sensitizing people to anything that might once again “wall off” the Bay’s shoreline. Planners and designers would be smart to inform themselves of the waterfront’s complex evolution, lest they propose something that has no chance of actually being built.

Unbuilt San Francisco is a collaborative effort of AIA San Francisco, Center for Architecture + Design, Environmental Design Archives at UC Berkeley, California Historical Society, San Francisco Public Library, and SPUR. The exhibition will be on display at various locations throughout the Bay Area through the end of November 2013. More information about specific dates and locations of showings can be found on the organizational websites linked above.

Mark Dreger is working towards his Masters in City and Regional Planning at UC Berkeley, concentrating in transportation and urban design. He is a San Francisco native and interested in the nexus between systems of mobility and the public realm. He can be reached at m.dreger@berkeley.edu.

The Small Indiscretions Of Lagos

An article in South Africa's Mail & Guardian boldly declares: “Nigeria's property boom is only for the brave.” Lagos is one of the continent's fastest urbanizing, rapidly expanding, bursting at the seams, oil-financed megacities. In this frenzy for investment, migration, and growth, Africa's amorphous--and apparently brave--middle class persists in jockeying for space in an exponential metropolis. So, too, does international real estate capital. Making space for its clean landing in Lagos demands at times the material expansion of the city, dredging the lagoon to build the new high-end enclaves of urban investment. And while real-estate interests demand firm ground, Lagos' slums barely stay afloat.

Source: http://theglobenewspaper.blogspot.com/2013/09/how-to-ensure-transparency-in-land-deals.html .

An article in South Africa's Mail & Guardian boldly declares: “Nigeria's property boom is only for the brave.” Lagos is one of the continent's fastest urbanizing, rapidly expanding, bursting at the seams, oil-financed megacities. In this frenzy for investment, migration, and growth, Africa's amorphous--and apparently brave--middle class persists in jockeying for space in an exponential metropolis. So, too, does international real estate capital. Making space for its clean landing in Lagos demands at times the material expansion of the city, dredging the lagoon to build the new high-end enclaves of urban investment. And while real-estate interests demand firm ground, Lagos' slums barely stay afloat.

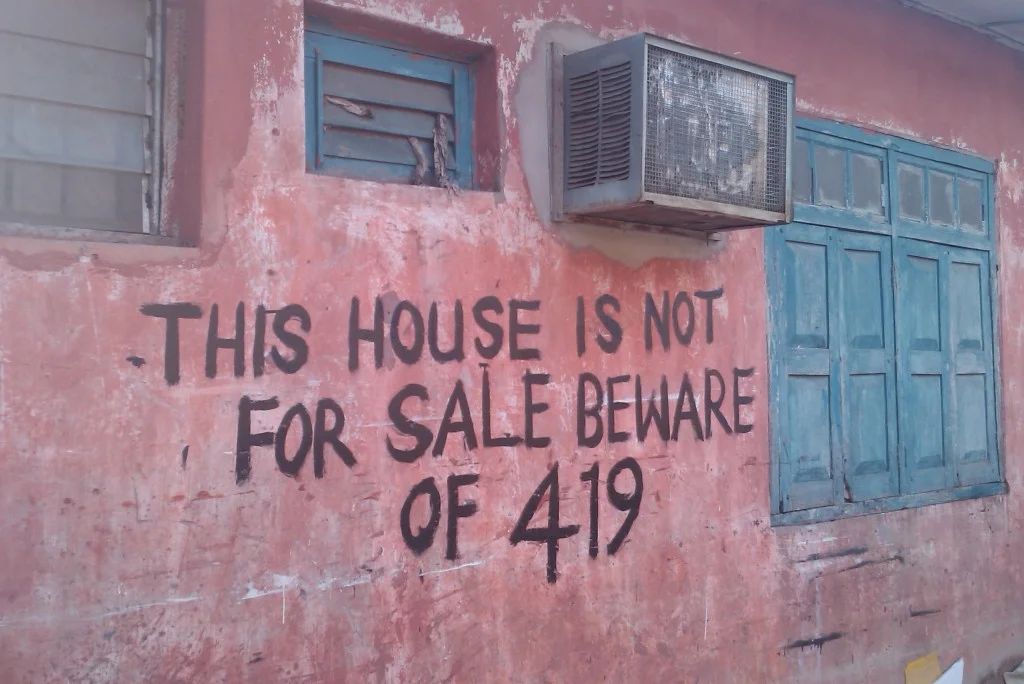

But space isn't enough. Congestion requires bravery, a necessary tool for navigating the uncertainty of Lagos’ land markets. To prove one’s bravery, the Mail & Guardian proposes a trial of agility: buy property in Lagos. The city's unhinged and impenetrable property record-keeping regime is reminiscent of public land holdings in North America's disorganized land management systems. Assuming they exist, Lagos’ land records are dispersed across multiple bureaucratic bodies and determining the validity of property ownershiprequires a laborious dive into the catacombs of municipal administration. This prompts awkward questions to your Lagos-based real estate agent: Do you even know who owns this building? This bureaucratic wall demands a similar fix to the ever-present problematic of African corruption: the transparency of land tenure. Instead, the 419 property scam abounds, where brokers successfully sell homes and land they do not own to unwitting buyers. A meticulous hustle that requires a fast pitch and often a forged title, the 419 scam is the illusion of trust, the predatory imitation of formality, and a stereotype of Nigerian technique.

But in the rush of urban life, trust is more expedient than validity. There is little time to find out what is real and trust will have to suffice. For those Nigerians unwilling to bet against uncertainty, the 419 has spawned a beleaguered, self-proclaimed lawyer who posts swindle avoidance advice on Nairaland. In 2010, with more 419-avoidance work than he could come to terms with, our lawyer falls apart: "I thought I knew every trick in the book and how to deal with them but they kept on coming at me like a heavy downpour and I couldn’t catch my breath in most situations. In fact it was so bad that I almost gave up handling property matters and questioned my competence in some instances." Lagos is underwater. This small public vestige of (fee-for-service) help can hardly keep his own head above water, let alone your property deals.

Our beaten-down west African private investigator shares his encounters with the 419 in a series of extravagantly informative vignettes replete with dodgy surveyors and GPS systems seemingly always on the fritz; subtle discrepancies in forged family deeds crafted by an insider mole; an un-earthing of the hidden remains of "buyers beware: not for sale" sign in the last minutes before a land-deal. Oh, the crushing suspense! Avoiding ruin requires constant vigilance and flexibility, something this intrepid lawyer (barely) manages to post publicly online. He is the public defender of proper land circulations, plugging the holes through which the 419 siphons off common capital.

Is this Nigeria? In Chimamanda Adichie's novel Americanah, the devastatingly insightful protagonist, Ifemelu, struggles with her identity as a been-to (that select group of young returnee Lagosians hungry to compare the city to elsewhere). Ifemelu writes in her blog, The Small Redemptions of Lagos: "Lagos has never been, will never be, and has never aspired to be like New York, or anywhere else for that matter... [Nigeria] is a nation of people who eat beef and chicken and cow skin and intestines and dried fish in a single bowl of soup, and it is called assorted, and so get over yourselves and realize that the way of life here is just that, assorted" (p. 421).

Met with the disparaging comments about North American blacks from fellow Nigerians, Ifemelu struggles to speak for either place:

Her Nigerian co-worker--a huge fan of the American show Cops--asks, "Why is it only black people that are criminals over there?"

To which Ifemelu, after a protracted silence, slowly responds: "It's like saying every Nigerian is a 419."

An amused retort: "But it is true, all of us have small 419 in our blood!"

Ifemelu gives up arguing with her co-worker, quits her job, and begins her new blog, a lyrical accounting of Lagos’ cityness emblazoned with a large, abandoned colonial mansion as its masthead. (I imagine this mansion with a hand-painted sign boldly inscribed on its facade: NOT FOR SALE). It is her return to Nigeria. It is not a relocation with an eye to elsewhere, but a feeling that "she had, finally, spun herself fully into being". Nearly unbundled by the constant re-education of this month's latest scam strategy, our own intrepid protagonist--the Nairaland Lawyer--persists, posts, and spins together his own income-generating position from the deluge of pleas for help from his online readers.

As the Mail & Guardian recounts, a solution to this exasperation and this bravery-in-the-face-of-uncertainty is the transparency of land laws. Routinization, organization, reliability: undifferentiated goods. Here, the security of tenure smooths out life for the West African middle class, opening new vistas of re-assuring liquidity for formal housing finance--no more borrowing from family, as you can finally borrow from the bank. Here, the security of tenure smooths out business for the global financial class, opening new landscapes of liquidity free from burdensome local uncertainties--no more worrying if your debtors will repay or if the deed you bought is legally attached to land.

Lagos is churning uncertainty into routine, but the city’s poorest residents are increasingly displaced. Nigerian architect Kunlé Adeyemi, alongside place-based community organizations, designed and built the first floating school in Lagos’ lagoon slum, Makoko. Prince Adesegun Oniru, the Commissioner for Waterfront and Infrastructure Development in Lagos State, responded by declaring the school illegal. He states, “The floating school has been illegal since inception…The simple answer to the floating school is that it is an illegal structure and it shouldn’t be there.” Since mid-2012, the government has been systematically demolishing Makoko, dispossessing the poor of their already tenuous claims to water-bound residence.

Lagos has a routine. It is a social infrastructure spun together by a series of “tentative cooperations based on trust.” These are the everyday negotiations of making life work in the exponential metropolis. The swindle is one part of this infrastructure, but does not represent it. The swindle violates it. If the formal routine--the new visibilities, formalities, and transparencies--succeeds in making urban life more durable for the African middle class, it will open the doors of institutional trust at the same time it drowns Makoko’s schools. It will stop all this needless spinning together, making work, and siphoning off. It will save Lagos from its own scam, but narrow the city’s robust assortment of life in the process.

Chris Mizes is a PhD student in City and Regional Planning at UCBerkeley. He is interested in landscape politics, infrastructure, land tenure, and African urbanisms. He blogs about his research interests at spacewithinlines and can be reached at mizes@berkeley.edu.

St. Louis’ Ballpark Village: Subsidizing the Status Quo

Some see the rising steel structures in downtown St. Louis as milestones in a long-awaited project, others as an unwelcome reminder: as construction on the Cardinals’ Ballpark Village becomes more visible, controversy surrounding the $650 million development has also grown.

Ballpark Village has been envisioned as a new downtown destination for over a decade, but like thousands of other developments nationwide, remained just a vision until earlier this year due to the recession. The 2007 plan included high-rise condominiums, bars, shops, restaurants, plus the introduction of a street grid intended to integrate the project into the surrounding downtown neighborhood. The current construction, however, will include none of the mixed-use features, and replaces much of the planned development with a bemoaned surface parking lot.

Some see the rising steel structures in downtown St. Louis as milestones in a long-awaited project, others as an unwelcome reminder: as construction on the Cardinals’ Ballpark Village becomes more visible, controversy surrounding the $650 million development has also grown.

Ballpark Village has been envisioned as a new downtown destination for over a decade, but like thousands of other developments nationwide, remained just a vision until earlier this year due to the recession. The 2007 plan included high-rise condominiums, bars, shops, restaurants, plus the introduction of a street grid intended to integrate the project into the surrounding downtown neighborhood. The current construction, however, will include none of the mixed-use features, and replaces much of the planned development with a bemoaned surface parking lot.

But is a Midwestern parking lot worth discussing within a larger planning context? The success of American cities in the 21st century has to a large extent come from the reclamation of - and reinvestment in - urban identities. Ballpark Village, by contrast, neglects downtown St. Louis’s urban character, which is increasingly dense, walkable, and home to a wealth of independent shops and restaurants. In ignoring the city’s resurgent urbanity, developers have also shown a disregard for St. Louis’s historical position as a major American metropolis, missing out on an unequivocal opportunity to showcase a nationally meaningful urban identity.

St. Louis, Missouri, is a city that has undergone multiple transformations, which map closely onto broader national trends. It has morphed from Mississippi trading post to peripheral Rust Belt manufacturing center, to glimmering site of the magnificent 1904 World’s Fair, to metropolis known for blight rather than bustle. In the last half-century, St. Louis became a laboratory for misguided urban renewal attempts that coincided with the construction of one of the nation’s most impressive monuments to modernism, the Arch. St. Louis’s urban fabric and population have also continuously been shaped by federal housing policy: the massive ambition of the Arch, appearing just a few years after the ill-fated construction of Pruitt-Igoe, one of the country’s most infamous housing projects, attest to the city’s synchronicity with nationwide sentiments and policy currents. Appropriately, Al Jazeera opinion writer Sarah Kendzior writes that in the 21st century, St. Louis has become “the gateway and memorial of the American dream.”

Today, St. Louis’ identity reflects each of these national epochs, but amajor piece of the city’s character comes not from its industrial history, housing projects, or architectural talking points. Instead, it draws from America’s favorite pastime—baseball. St. Louis’ relationship with its baseball team, like many American cities', is a historic relationship closely tied to the city’s identity and a source of pride. The Cardinals’ Busch Stadium, located centrally in a downtown area, is a boon to the city. Frequent ballgames draw spirited crowds, who often venture outside the ballpark to downtown restaurants and fill area bars following both raucous wins and disappointing losses.

Rebuilt in 2006, Busch Stadium was unusual in that it was financed predominantly by the Cardinals’ private funds (nearly 90%). The city did, however,cover a local admissions tax on tickets, as well as assist with initial public infrastructure costs. There’s no doubt that the construction of the new stadium in 2006 was a worthwhile investment with a sizable return for the city. But does this justify the team’s newest endeavor?

The reality of the project today, after six years of delay and economic uncertainty, is far less ambitious than that initially proposed. The development’s first phase is now slated to offer a baseball history museum, a “Cardinals Nation” restaurant, a cowboy bar, and a two-story “Budweiser Brew House.”

An early plan for the development shows the introduction of six city blocks. Source: nextSTL

An early 2013 plan also shows the diminished street grid and the replacement of housing and retail with surface parking. Source: nextSTL