Landscapes of Abundance… or Debt & Decay?

/Greece. The word brings to mind a dazzling array of images. Whitewashed houses topped with cobalt blue roofs. Windmills and grape vines. Anthony Quinn dancing with a glass of ouzo by the sea. Yet what the word does not automatically trigger is desperate landscapes comprised of abandoned, half-constructed homes.

This article explores the vernacular architecture of Greece (in particular the island of Santorini), and also investigates such landscapes in times of economic debt & crisis. As the US government finally reaches a deal to end government shutdown and avoid default, we can look to other countries for precedents regarding how debt crises affect building, planning and constructed landscapes at the local level. This isn’t an alarmist cry against the certainty of a debt-ridden future. Instead, I tracethe possibilities of how debt affects the built environment, and ask if we should begin thinking about parallel models and case studies. Although Greece and its islands may comprise a much smaller geographic scale than the US or Canada, it is an instructive example and microcosm that we can learn from.

Greece’s ongoing debt crisis was triggered by the 2008 recession and resulted from a confluence of factors: 1) government deficit 2) government debt and 3) the structural weakness of the Greek economy. While the crisis drastically impacted Greek employment, tourism, and Euro exchange rates at the macroeconomic level, it also had a far more micro effect on Greeceat the local level. Examples of these incremental and parochial consequences come from the Greek Islands, where the effects of the recession are amply visible to the naked eye.

While driving and hiking around the Cyclades and the Dodecanese, one significant element in the fabric that I quickly noticedwas the striking amount of half-constructed buildings and homes (primarily residential building types). This was most apparent on the island of Santorini, readily apparent in the semi-rural areas removed from the tourist centers of the island. I found the contrast to be unsettling and raised important questions about urban and rural development on the island. How could so many buildings be left unfinished?

Santorini, in particular, is known for its whitewashed roof vault construction. The particular building type is an important bioclimatic adaptation—the whitewash aids in the albedo effect, a passive cooling technique. The cave vaults also help keep the houses cool in the summer, as the earth dampens the diurnal and annual temperature fluctuations. In addition, such vaulted cave houses were often built into the earth around them, saving the need for extra materials and reducing space needs. The Cycladic islands naturally have scarcity of timber, although the island is blessed with an abundance of rich volcanic soil.

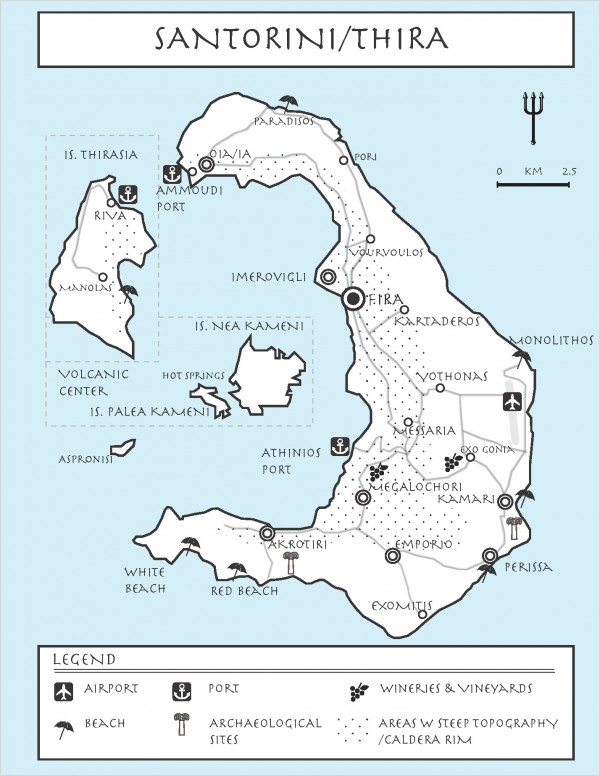

The island is crescent-shaped, and is actually an active volcano. Its volcanic nature is thought to have led to the demise of the Minoan civilization in Akrotiri at the south end of the island in mid-second millennium BCE. The island has often served as basis for the myth of Atlantis, as Plato recounts many similarities between the two places. The rich volcanic soil of the island has led to the harvesting of vegetables and fruit, in particular grapes for local assyrtiko and vinssanto wines, cherry tomatoes, fava beans and white eggplants. These local foods have become the foundation for the island’s popular gastronomic scene.

With its unique crater formation, the island has served as a mecca for tourism since the 1800s. Its natural viewsheds have created amphitheatric locations for towns such as Oia, Fira and its highest point, Venetian-settled Imerovigli. The rest of the island slopes down gradually from the caldera rim to the sea, and it is here on the eastern and southern ends of the island that you find an abundance of half-developed homes.

I asked our local guides, Yiannis and Paros, aboard a sailing trip that circumnavigated the island, why there were so many half-constructed homes (masonry and concrete structure present but lacking plaster or interior finishing). Paros answered that this was primarily a result of the economic recession—residents hadbegun the construction of homes, and then did not have the finances to finish them. Additionally, Paros mentioned that many of the partially finished buildings were illegal homes. Construction had stopped, as they did not have the requisite building permits from the government to continue. This also relates back to economic hardship, as proper permitting is often expensive and time-consuming.

Despite claims that Santorini managed to completely circumvent the negative effects of the recession, I remain unconvinced. How can one side of the island—the whitewashed rim with its vibrant architecture—look so profoundly magical, while the other seems desolate and abandoned? This was not the Greece I was expecting. The island had revealed a duplicitous nature—one side based on the bustling tourism industry, and the other suffering under the harsh, local reality prompted by the economic crisis.

Now, after 3 years of economic crisis, the Greek economy is beginning to stabilize. Whether or not some of these half-constructed buildings will be adaptively ‘re-used’ is a major question still to be answered. In a similar forlorn way, these abandoned, empty homes reminded me of the foreclosure crisis experienced here in the US. Is there a way to move forward with building from a sustainability standpoint? What can Greece learn from the foreclosure crisis in the US, and the US learn from the debt crisis in Greece?

Nicola Szibbo is a PhD candidate in the Department of City and Regional Planning at UC Berkeley. Her interests include vernacular architecture, green neighborhood rating systems and sustainable urban design in Europe, Canada & the United States. You can reach her at nszibbo@berkeley.edu.