The Small Indiscretions Of Lagos

Source: http://theglobenewspaper.blogspot.com/2013/09/how-to-ensure-transparency-in-land-deals.html .

An article in South Africa's Mail & Guardian boldly declares: “Nigeria's property boom is only for the brave.” Lagos is one of the continent's fastest urbanizing, rapidly expanding, bursting at the seams, oil-financed megacities. In this frenzy for investment, migration, and growth, Africa's amorphous--and apparently brave--middle class persists in jockeying for space in an exponential metropolis. So, too, does international real estate capital. Making space for its clean landing in Lagos demands at times the material expansion of the city, dredging the lagoon to build the new high-end enclaves of urban investment. And while real-estate interests demand firm ground, Lagos' slums barely stay afloat.

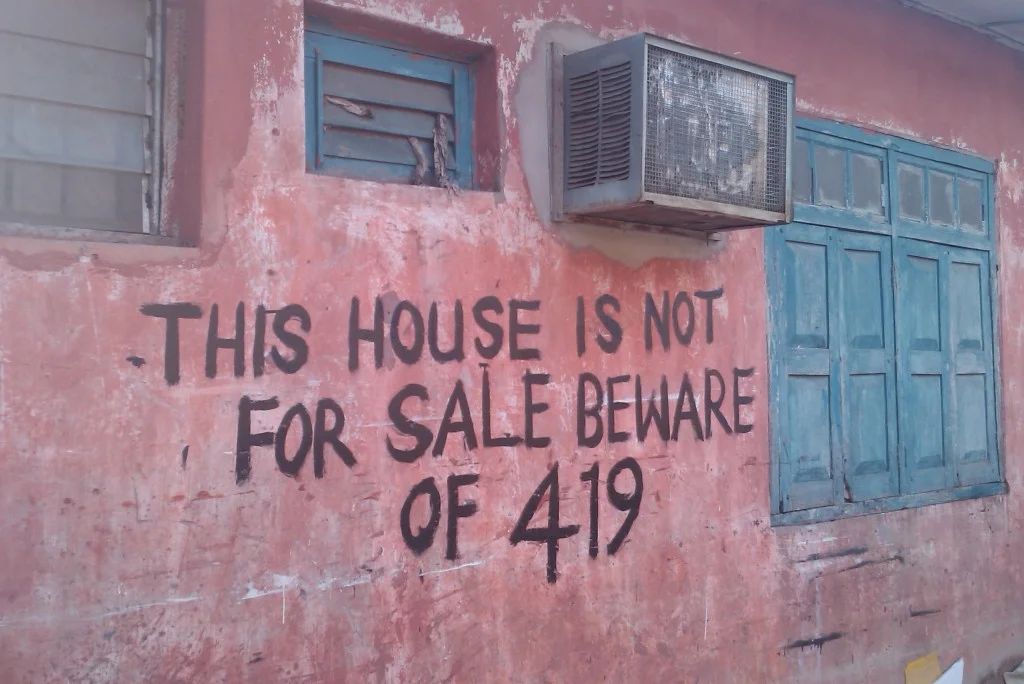

But space isn't enough. Congestion requires bravery, a necessary tool for navigating the uncertainty of Lagos’ land markets. To prove one’s bravery, the Mail & Guardian proposes a trial of agility: buy property in Lagos. The city's unhinged and impenetrable property record-keeping regime is reminiscent of public land holdings in North America's disorganized land management systems. Assuming they exist, Lagos’ land records are dispersed across multiple bureaucratic bodies and determining the validity of property ownershiprequires a laborious dive into the catacombs of municipal administration. This prompts awkward questions to your Lagos-based real estate agent: Do you even know who owns this building? This bureaucratic wall demands a similar fix to the ever-present problematic of African corruption: the transparency of land tenure. Instead, the 419 property scam abounds, where brokers successfully sell homes and land they do not own to unwitting buyers. A meticulous hustle that requires a fast pitch and often a forged title, the 419 scam is the illusion of trust, the predatory imitation of formality, and a stereotype of Nigerian technique.

But in the rush of urban life, trust is more expedient than validity. There is little time to find out what is real and trust will have to suffice. For those Nigerians unwilling to bet against uncertainty, the 419 has spawned a beleaguered, self-proclaimed lawyer who posts swindle avoidance advice on Nairaland. In 2010, with more 419-avoidance work than he could come to terms with, our lawyer falls apart: "I thought I knew every trick in the book and how to deal with them but they kept on coming at me like a heavy downpour and I couldn’t catch my breath in most situations. In fact it was so bad that I almost gave up handling property matters and questioned my competence in some instances." Lagos is underwater. This small public vestige of (fee-for-service) help can hardly keep his own head above water, let alone your property deals.

Our beaten-down west African private investigator shares his encounters with the 419 in a series of extravagantly informative vignettes replete with dodgy surveyors and GPS systems seemingly always on the fritz; subtle discrepancies in forged family deeds crafted by an insider mole; an un-earthing of the hidden remains of "buyers beware: not for sale" sign in the last minutes before a land-deal. Oh, the crushing suspense! Avoiding ruin requires constant vigilance and flexibility, something this intrepid lawyer (barely) manages to post publicly online. He is the public defender of proper land circulations, plugging the holes through which the 419 siphons off common capital.

Is this Nigeria? In Chimamanda Adichie's novel Americanah, the devastatingly insightful protagonist, Ifemelu, struggles with her identity as a been-to (that select group of young returnee Lagosians hungry to compare the city to elsewhere). Ifemelu writes in her blog, The Small Redemptions of Lagos: "Lagos has never been, will never be, and has never aspired to be like New York, or anywhere else for that matter... [Nigeria] is a nation of people who eat beef and chicken and cow skin and intestines and dried fish in a single bowl of soup, and it is called assorted, and so get over yourselves and realize that the way of life here is just that, assorted" (p. 421).

Met with the disparaging comments about North American blacks from fellow Nigerians, Ifemelu struggles to speak for either place:

Her Nigerian co-worker--a huge fan of the American show Cops--asks, "Why is it only black people that are criminals over there?"

To which Ifemelu, after a protracted silence, slowly responds: "It's like saying every Nigerian is a 419."

An amused retort: "But it is true, all of us have small 419 in our blood!"

Ifemelu gives up arguing with her co-worker, quits her job, and begins her new blog, a lyrical accounting of Lagos’ cityness emblazoned with a large, abandoned colonial mansion as its masthead. (I imagine this mansion with a hand-painted sign boldly inscribed on its facade: NOT FOR SALE). It is her return to Nigeria. It is not a relocation with an eye to elsewhere, but a feeling that "she had, finally, spun herself fully into being". Nearly unbundled by the constant re-education of this month's latest scam strategy, our own intrepid protagonist--the Nairaland Lawyer--persists, posts, and spins together his own income-generating position from the deluge of pleas for help from his online readers.

As the Mail & Guardian recounts, a solution to this exasperation and this bravery-in-the-face-of-uncertainty is the transparency of land laws. Routinization, organization, reliability: undifferentiated goods. Here, the security of tenure smooths out life for the West African middle class, opening new vistas of re-assuring liquidity for formal housing finance--no more borrowing from family, as you can finally borrow from the bank. Here, the security of tenure smooths out business for the global financial class, opening new landscapes of liquidity free from burdensome local uncertainties--no more worrying if your debtors will repay or if the deed you bought is legally attached to land.

Lagos is churning uncertainty into routine, but the city’s poorest residents are increasingly displaced. Nigerian architect Kunlé Adeyemi, alongside place-based community organizations, designed and built the first floating school in Lagos’ lagoon slum, Makoko. Prince Adesegun Oniru, the Commissioner for Waterfront and Infrastructure Development in Lagos State, responded by declaring the school illegal. He states, “The floating school has been illegal since inception…The simple answer to the floating school is that it is an illegal structure and it shouldn’t be there.” Since mid-2012, the government has been systematically demolishing Makoko, dispossessing the poor of their already tenuous claims to water-bound residence.

Lagos has a routine. It is a social infrastructure spun together by a series of “tentative cooperations based on trust.” These are the everyday negotiations of making life work in the exponential metropolis. The swindle is one part of this infrastructure, but does not represent it. The swindle violates it. If the formal routine--the new visibilities, formalities, and transparencies--succeeds in making urban life more durable for the African middle class, it will open the doors of institutional trust at the same time it drowns Makoko’s schools. It will stop all this needless spinning together, making work, and siphoning off. It will save Lagos from its own scam, but narrow the city’s robust assortment of life in the process.

Chris Mizes is a PhD student in City and Regional Planning at UCBerkeley. He is interested in landscape politics, infrastructure, land tenure, and African urbanisms. He blogs about his research interests at spacewithinlines and can be reached at mizes@berkeley.edu.