Leveraging Large Scale Development for Equity and Sustainability?

The Oakland waterfront redevelopment project called Oak to Ninth is back in the news after Governor Brown and Mayor Quan recently secured $1.5 billion in funding from a Chinese investment company. The Oakland’s City Council approved the project and a Community Benefits Agreement (CBA) in 2006, but the developer, Signature Properties, never broke ground due to the recession. In 2011, city officials even tried (and failed) to attract the planned satellite campus of Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory to the site. Now, the development is proceeding with a new name: Brooklyn Basin.

Like fees and exactions, CBAs represent a developer’s contribution to the local community as a condition of receiving public subsidies and permits. Going beyond baseline payments for infrastructure such as roads and schools, CBA campaigns can target affordable housing and workforce development, among other local needs. They can involve diverse stakeholders, as well as more immediate input from the public than fees and exactions, which may be assessed automatically.

Oak to Ninth put equity advocates and the developer in an unlikely alliance. Once the City and the developer had signed a development agreement that included community benefits and enforcement provisions, community groups came out to planning meetings to support the project. This placed them at odds with environmentalists, intent on maintaining an earlier agreement with the city that created a greater amount of public open space from the former industrial site, as well as historic preservationists who wanted the whole Ninth Street Terminal, not part of it, restored.

Today, Plan Bay Area and other efforts to promote smart growth in the region suggest that environmental and social justice groups are much less at odds with each other. This is partly due to a greater aligning of goals between environmental groups and organizations focused on social justice and community development. The former have focused their agenda more on urban issues, in addition to wildlife preservation outside cities. The latter have focused on health and opportunities in the green economy. Both have come together around the uneven impacts of climate change.

With Oak to Ninth-Brooklyn Basin and its accompanying CBA looking set to move forward again, it’s worth checking in with the overall concept of community benefits. In the time that Oak to Ninth lay dormant, CBAs were tested, shown to have some fundamental weaknesses, and improved upon. The foreclosure crisis and a new drive to link sustainability with housing and land use under Plan Bay Area provide a different backdrop for the project than the pre-recession real estate market did.

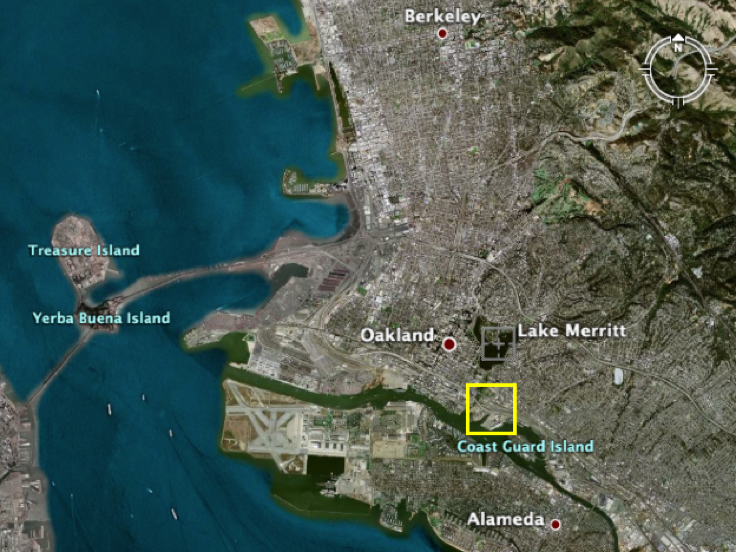

At 30 acres, Brooklyn Basin is small compared to other large-scale infill projects such as the Railyards in Sacramento (240 acres), the future terminus of California’s high-speed rail line, or the Brooklyn Navy Yards in New York (300 acres). Yet Brooklyn Basin will be significant for reconnecting Oakland neighborhoods south of Downtown with the waterfront. The site borders Chinatown, Lower San Antonio, and Fruitvale, where there are high poverty rates and a need for jobs and affordable housing.

Brooklyn Basin plaN (Signature Properties 2013, http://www.brooklynbasin.com/images/sitemap.jpg)

In the seven years since the Oak to Ninth project approval and CBA campaign, Oakland has experienced high foreclosure rates, rising unemployment, and social movements targeting income and housing inequality, such as Occupy Oakland. Developer funding for job training programs and affordable housing stalled along with the Oak to Ninth project. However, as soon as the first building permit is issued on the multi-year project, $1 million will be divided among several Oakland job-training programs, with another $325,000 specifically for job training in Chinatown, Fruitvale and Lower San Antonio. In terms of housing, 465 affordable units will be built onsite-- about 17 percent of a total 2,765 units.

Oak to Ninth was approved at a time when CBAs were becoming a popular tool for equity advocates. CBAs provide a political rallying point for sharing the benefits of publicly funded projects, rather than simply halting them. The Staples Center CBA (2001) is considered an early model for community groups to negotiate for first source hiring, living wage, and affordable housing when large public subsidies for development are at stake. Yet CBAs can also reflect broader power imbalances. Who represents the “community” can come up for debate, as it did with the Atlantic Yards CBA (2005).

The Oak to Ninth CBA was grassroots-driven. A group of labor, neighborhood, faith-based and equity advocates were among the coalition members who created political pressure for the City of Oakland to approve the development agreement that codifies the CBA. The City of Oakland, eager to attract development, was a reluctant partner in the CBA, but eventually signed a development agreement that is binding for both the City and the developer. Among the agreement’s safeguards are payroll reporting by contractors and financial penalties if targets are not met.

The local hiring provisions of the CBA are designed to help Oakland workers without significant previous experience break into the construction trades. It does this by requiring that six percent of the job hours on individual parcels be carried out by Oakland residents who are new to the construction trade, with an incentive to keep the same workers on the job for the equivalent of 23 full time weeks. Although this is only a small percentage of the site hours, the effect will be that at least a third of the apprenticeships – paid, entry level, career path positions - on each project site will be filled by Oakland residents.

CBAs have become more common since Oak to Ninth, and with more examples have come lessons for their proponents. Enforcement mechanisms are key, and the most effective CBAs provide a stepping-stone to stronger citywide policies on local hiring and affordable housing, rather than project-by-project funding. Although a more comprehensive citywide policy on community benefits has not materialized in Oakland, members of the Oak to Ninth CBA coalition have put the experience they gained to use. In 2012, EBASE helped negotiate a stronger CBA in connection to the redevelopment of the Oakland Army Base. The site will remain industrial, creating construction as well as long term living wage shipping and logistics jobs for Oakland residents and residents of the high unemployment area of West Oakland.

The loss of state funding has complicated local redevelopment, but public funding and permitting of large-scale development remains a leverage point for equity and sustainability advocates. As it moves forward, the Brooklyn Basin project will provide much-needed local investment, but work remains to be done to make housing and employment more equitable in Oakland and in the Bay Area across the board.

Lizzy Mattiuzzi is a doctoral candidate in City and Regional Planning at UC Berkeley. She studies the politics of sustainable land use, transportation, and community development at the urban and metropolitan scales. She can be reached at emattiuzzi@berkeley.edu.