New York City’s High Line: Is an Evaluative Framework Problematic in the Public Sector?

As we become more cynical of the federal government’s ability to get things done, there is a growing movement to empower cities to step up and take more control over their own economic destinies by “measure[ing] what matters.”

Measurement[1] is often carried out under an evaluation framework that is set up to identify priority areas for growth and then determine progress toward reaching the desired outcome. Evaluation frameworks are one of several tools appropriated from the private sector that bring a data-driven approach into the public sector (and also, increasingly, in the nonprofit sector).

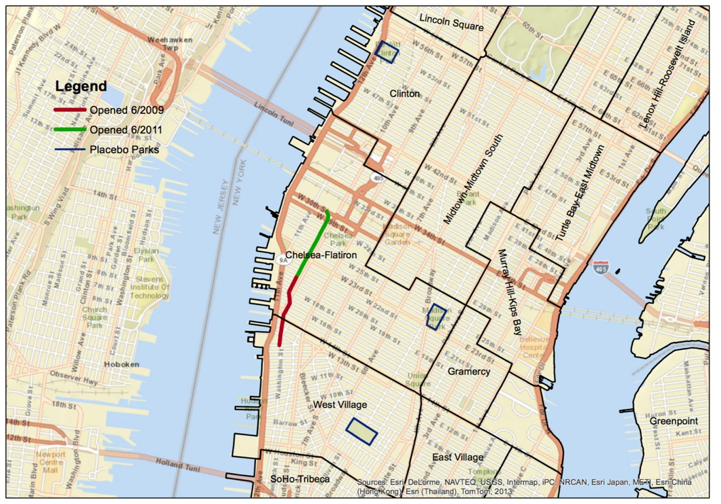

Map of New York City's High Line and Surrounding Neighborhoods. SOURCE: Michael Levere, Department of Economics, UC San Diego

The High Line – a nearly one-and-a-half-mile linear park in Manhattan built on an elevated section of a disused railroad trestle – is a useful case in considering both the effectiveness and problems of an evaluative framework. The park was completed in New York City during the Bloomberg administration[2] - Bloomberg had, of course, been founder, CEO, and owner of Bloomberg L.P. prior to his election as mayor. Of his many contributions, Bloomberg brought the rigors of “evaluation” into many areas of his administration, including the planning department.

The original planning framework for the High Line was developed in 2002 by Friends of the High Line and takes a fairly balanced approach to acknowledging competing needs for the space. The plan proposes balancing preservation with growth. It includes input from community members wanting to preserve the existing character of the neighborhood and to create affordable housing.

NYC planning director at the time, Amanda Burden, told the New York Times in 2012: “I like to say that our ambitions are as broad and far-reaching as those of Robert Moses, but we judge ourselves by Jane Jacobs’s standards.”

However, a combination of factors resulted in an outcome more apropos of Moses than Jacobs. One factor was the rezoning along the High Line, which came as a result of a strong push from property owners. No affordable housing requirement was set, further contributing to increase in property values along the high line and gentrification.[3]

An additional factor was the evaluation approach taken by the Bloomberg administration. Out of the data-driven corporate environment emerged PlaNYC, a sustainability plan launched in 2007 that created an evaluative framework for sustainability as part of city development policy.

The Open Space Sustainability Indicators below from the 2010 plan show a deceptively simple goal for park space in the city and how it was measured.

PlaNYC 2010 Open Space Sustainability Indicators

The goal is essentially to measure success through distance of residence from the park, with the High Line an example of a park helping to achieve this goal. The city planned to look at what portion of New Yorkers live within ¼ mile (goal: 85%) and a ½ mile (goal: 99%) of a park or playground.

Close proximity to the High Line has generally increased property values in the adjacent neighborhoods. And the High Line has been good, economically speaking, for the city. But the park is clearly not benefiting the members of the original neighborhood to that extent that it could because it is now too expensive for original residents and has brought in a different character of economic activity.

Of course, officials and other parties responsible for the High Line were not acting in lockstep from an evaluation framework at every point in their process. However, the measurable goal for open space in the 2010 plan belies what was most important to accomplish. Ideally, city governments have a responsibility through their economic development plans to shape the urban environment in ways that work for everyone, rather than a small few.

NOTES:

[1] What is meant by “measuring what matters” in this economic development context is that cities step up to build up their own local economies by essentially determining their own economic development priorities and ultimately reshaping the local urban environment.

[2] The High Line was completed during Mayor Bloomberg’s term except for the third and northernmost section section of the park, the High Line at the Rail Yards, which opened to the public on September 21, 2014.

[3] While it is difficult to assess the extent to which the High Line played a role in contributing to gentrification in surrounding neighborhoods, we do know from recent research by an economist at UC San Diego that the opening of the High Line led to a large increase in home values, both the year after the park opened and also close to the park opening in 2008 and 2009 possibly in anticipation to the park opening. The Guardian discusses the High Line as an example of “environmental gentrification” – the growing phenomenon of rising property values in the wake of a large-scale urban greening project. The New York Times also describes gentrifying factors.

Rebecca Coleman is a Masters student in the Department of City and Regional Planning focusing on housing, community, and economic development. Before graduate school, she worked as a program manager at a nonprofit consulting firm in Boston on an initiative to improve life outcomes for black men and boys. Rebecca holds a B.A. and a B.S. from UC Berkeley.