Vestiges of San Francisco’s Unbuilt Waterfront

/San Francisco has oftenserved as a blank canvas since its rapid rise to prominence after the Gold Rush in the mid-1800s – the subject of countless visions for how the built environment should be designed. Whilesomewereoutlandish and others more grounded, the many ideas advanced over the years for guiding the City’s development have each presented a roadmap for moving forward, complete with nested values of what is most important for the future. Such is the subject ofUnbuilt San Francisco – an exhibit currently presented at five locations around the Bay Area, including at UC Berkeley (more details below). On display are plans, renderings, models, and other media depicting unrealized visions for the San Francisco Bay Area. Some of these proposals, such as a BART line running into Marin County, many wish had been built; others, like Marincello, a 30,000-person community in the now-preserved Marin Headlands, we cannot imagine advancing today. The exhibit covers a journey of great breadth, ultimately leaving the viewer with anuneasy sense of what could have been.

In the 1960s, a large planned development was proposed to be built in the Marin Headlands by the Gulf Oil Corporation. In the face of strong opposition from various environmental groups, in 1972, the company reluctantly sold the land so it could be incorporated into a new national park – the Golden Gate National Recreation Area. Source: Thomas Frouge, developer

The lasting impact of the Unbuilt San Francisco exhibition, though, is not simply an understanding of the Bay Area’s various unrealized futures, but more fundamentally an appreciation of how the choices made in the past impact how we see things today.

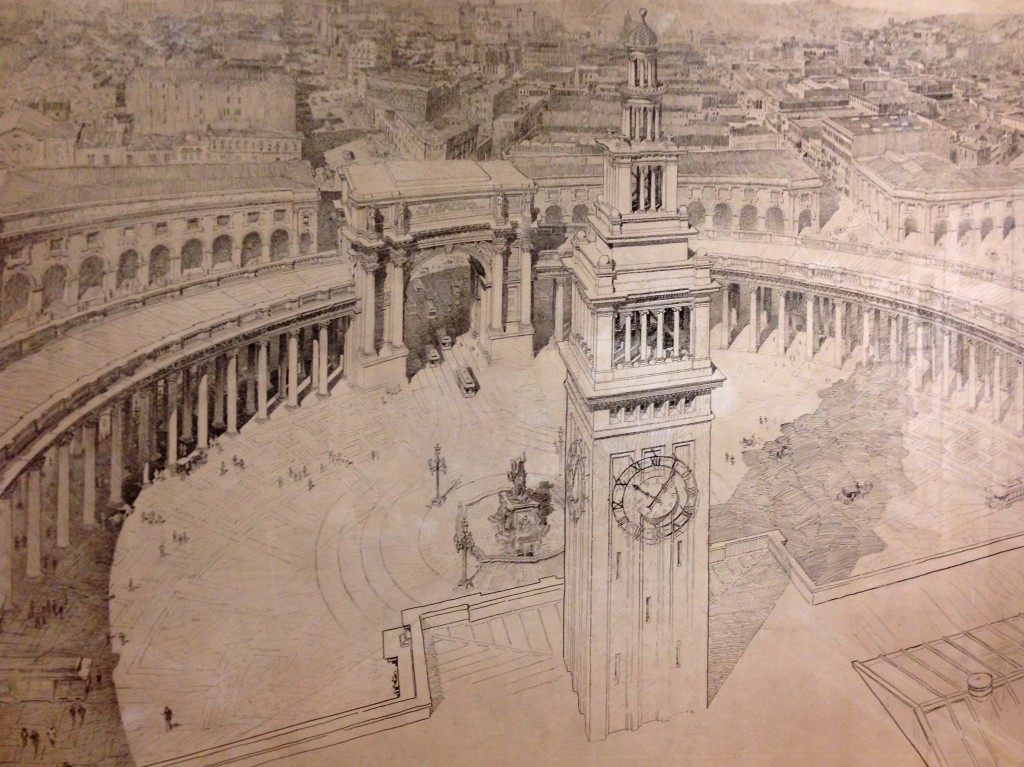

San Francisco’s ever-evolving waterfront is an excellent case study. Indeed, the edge of the Bay might have turned out quite differently than what we see today. A turn-of-the-century plan imagined the Ferry Building at the foot of Market Street surrounded by towering Roman-style columns. Decades later, another would have replaced San Francisco’s beloved waterfront monument with a modernist-inspired World Trade Center, surrounding a large sun dial. These ideas may sound outlandish today, but they were seriously considered at the time.

This turn-of-the-century vision would have created a grand public space in front of the Ferry Building encircled by classically-styled columns and arches. Source: Willis Polk (1897)

Another vision would have done away with the Ferry Building altogether and replaced it with a modern World Trade Center. The slender center tower and sun dial seem to allude to the structures they would have replaced. Source: Joseph H. Clark (1951).

One idea in particular has had an enduring influence on how we envision the waterfront today: the proposal for an elevated high-speed motorway running the length of the Bay’s shoreline.

In the 1950s, following the national trend, an ambitious network of limited-access freeways was conceived for San Francisco, crisscrossing all corners of the 7-by-7-mile city. Despite being swept up by the freedoms of automobility, freeways were far from welcomed in San Francisco. As the first few structures went up, including the double-decker Embarcadero rising between Market Street and the Ferry Building, people began to realize the damaging effects the roads were having. In swift response, the now famous Freeway Revolt was born.

Citizens crowd into City Hall wearing signs on their heads to express their opposition to the freeways being erected all over San Francisco. Source: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library.

Freeways in San Francisco were opposed for various reasons, but much of the discourse centered on aesthetics and access. Beyond being unsightly, neighborhoods that received the early motorways were walled off from their surroundings and quickly succumbed to blight and loss of vitality. After years of fierce opposition, the citizens' revolt was ultimately successful in blocking most proposed freeways, and the Embarcadero was only partly completed (it was originally proposed to connect with the Golden Gate Bridge). Just 21 years after the Embarcadero’s completion, it took only seconds for the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake to damage the structure enough to warrant taking it down. Though many enjoyed the access it provided and called for reconstruction, then-Mayor Art Agnos envisioned a new aesthetically-pleasing waterfront, and fought for the freeway to be replaced with the grand boulevard we know today. Few look back longingly.

Citizens crowd into City Hall wearing signs on their heads to express their opposition to the freeways being erected all over San Francisco. Source: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library.

The unrealized vision for a complete freeway network in San Francisco has left citizens sensitized not only to future roadway proposals, but also to any project that might possibly impact the waterfront’s aesthetics, access, or views. One need look no further than the controversial 8 Washington project rejected by voters earlier this month – what would have been a 134-unit luxury condominium development along the waterfront, adjacent to where the Embarcadero Freeway used to stand – to see this. The project had diverse opposition – from those who questioned building $5 million condos in a city struggling to provide affordable housing,to those who criticized its parking ratios – but most discourse concerned appearance and accessibility. Critics focused on the project's 13-story height, roughly twice that of the late freeway, claiming it would have blocked views and access to the Bay, thereby tarnishing the waterfront’s appeal.

This rendering, drawn up by supporters of 8 Washington, takes an elevated perspective, showing the tall buildings of the Financial District in the background, to downplay the project’s heights.

The opposition's image instead takes a ground-level perspective, juxtaposing the Embarcadero Freeway in front of 8 Washington, to illustrate the development’s towering design.

In typical San Francisco fashion, the 8 Washington debate became so heated that it was the subject of not one but two propositions on the November ballot earlier this month. Voters were asked if they approved of the decision to allow the project to exceed existing height limits. The ‘No on B & C’ campaign strategically employed the slogan “No Wall on the Waterfront” and made direct comparisons to the Embarcadero Freeway (campaign ad embedded below). Former Mayor Art Agnos reemerged as a spokesperson for the opposition, proclaiming that “8 Washington will be the first brick in a new wall along the waterfront.” Despite the obvious differences between the fallen freeway and 8 Washington, people were concerned that the progress made along the waterfront in recent years would be lost if the proposal moved forward. Ultimately, both initiatives were soundly voted down almost two-to-one. The developer may choose to return with a new down-sized proposal, but at least this version of 8 Washington joins the list of San Francisco’s unrealized visions.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cujWdElxCHk#action=share

Ideas remain unrealized for many reasons – because they do not match prevailing values, they were not well-conceived, or perhaps they just were not well-articulated – but some nevertheless persist, influencing decision-making to this day. The many unbuilt visions for San Francisco’s waterfront have not only influenced what was actually built, but have left a more enduring impact on how people imagine its possible futures. Turning over the waterfront to the purely utilitarian role of moving automobiles was ultimately rejected, replaced by a more aesthetically-focused public space. The discourse surrounding this unbuilt vision continues, sensitizing people to anything that might once again “wall off” the Bay’s shoreline. Planners and designers would be smart to inform themselves of the waterfront’s complex evolution, lest they propose something that has no chance of actually being built.

Unbuilt San Francisco is a collaborative effort of AIA San Francisco, Center for Architecture + Design, Environmental Design Archives at UC Berkeley, California Historical Society, San Francisco Public Library, and SPUR. The exhibition will be on display at various locations throughout the Bay Area through the end of November 2013. More information about specific dates and locations of showings can be found on the organizational websites linked above.

Mark Dreger is working towards his Masters in City and Regional Planning at UC Berkeley, concentrating in transportation and urban design. He is a San Francisco native and interested in the nexus between systems of mobility and the public realm. He can be reached at m.dreger@berkeley.edu.